In the third episode of Israel Story, we’ve got three stories that all revolve around people who rescue books, chase after books, or otherwise allow books to determine their destiny—from a Yiddish book collector based in the Tel Aviv central bus station to a lonely college student to bibliophiles in search of the lost fragments of the Aleppo Codex.

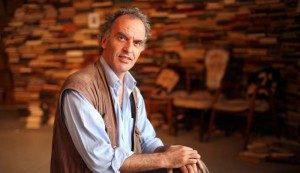

First, a chat with Israeli writer Etgar Keret, who has some original thoughts on where the “people of the book” tagline came from.

Mishy Harman (narration): When we walked into Etgar Keret’s apartment in Tel Aviv, to talk to him about the theme of our episode today, “People of the Book,” his wife Shira and their eightyearold son Lev were in the kitchen making a cake. The mixer was mixing, the blender was… blending, and the spatula was constantly clanking against the bowl as Lev was trying to sneak in some licks. You know, basically the perfect ingredients for a radio recording.

We wanted to talk to Etgar not only because he’s one of Israel’s leading authors, the “voice of our generation,” people often say, but also because he has this reputation of being the first Israeli author to fully disengage from the Bible. To write in an utterly ‘secular Israeli’ style, whatever that means.

Anyway, back to the ruckus… Etgar suggested that we go into Lev’s room, which we did. But there too there was this constant hum, like a motor running or something.

Turns out it was the oxygen pump in Lev’s fishtank. We asked if we could turn it off for a few minutes but Lev looked kind of worried. He explained that Goldie, the goldfish, was five years old, which, apparently, is four years beyond the average goldfish life expectancy, and he needs all the oxygen he can get. So, there we were, with probably the oldest goldfish in Tel Aviv looking on, discussing how it is that a really old book became the tagline of the Jews.

Mishy Harman: What does that even mean to be the ‘People of the Book’?

Etgar Keret: Well you know, I think that many people think that, you know, being the ‘People of the Book’ means that we, we read lots of books. [Mishy laughs]. But you know… But it refers only to one book, and I think that there is something about the Bible, because it is a text and it is very abstract in its nature, and it talks about an abstract God, then we talk about the book, because we cannot talk about the cross, you know, or we cannot talk about something that is very very concrete, so we say: “You know, the book, the book, you know.” [Etgar and Mishy laugh].

Mishy Harman: Do you think that there’s something a little bit selfcongratulatory about us calling ourselves the ‘People of the Book’? Like, you know, I think being the ‘People of the Book’ is probably a bit better than like being the ‘People of the GameBoy’ or the ‘People of the Sony Playstation’ or something like that, right? So do you think we’re actually trying to say like “ah, you know, we’re kind of serious, we’re the ‘People of the Book’”?

Etgar Keret: I think that we became the ‘People of the Book’ just for lack of any other object to use. I’m saying branding Jews as the ‘People of the Book,’ you know, people from Islam can come and say, “we are also the ‘People of the Book,’ we just have a different book, you know, it’s called Koran, but we’re also the ‘People of the Book’ you know?”

I can imagine that there were a bunch of copywriters in the room, and they said, “how about we call ourselves the ‘people who cut the top of their penises off?’” And you know, and somebody said: “You know, I don’t think it’s gonna work, you know I don’t think it’s gonna work. Let’s go something you know allofthefamily kind of thing, let’s go for the ‘People of the Book.’” And they went with him, and maybe it was a smart decision.

Mishy Harman (narration): Hey, I’m Mishy Harman, and welcome back to Israel Story, or Sipur Israeli, here on Vox Tablet. Each episode we have a theme and a few stories that relate to it. Thanks to the ingenuity of the Talmudera Don Drapers, today’s theme is not the people who cut off the tops of their penises… Instead, we’ve got three stories that all revolve around books. And lest you feel that you already maxed out lately on hearing about the Bible, I can tell you that only one of the stories today is about The Book, and even that one… well, not really. In today’s episode we’ll visit this weird, funky Yiddish time capsule; We’ll see how stealing a book from a public library can determine who you marry; And finally, we’ll end up in Syria, in Aleppo, and meet a secret underground of ‘bookies’ who are obsessed with what the New York Times called a “High Holy Whodunit.” But before all that, back to Etgar.

Mishy Harman: So Etgar, let’s imagine: If you were the Minister of Education, or the Prime Minister, or… or, you know, a dictator, and you could make all Israelis read one book, what book would you choose?

Etgar Keret: Well, first of all I like the idea of being a dictator. You know, it’s a nice idea, thank you for sharing it with me, Mishy. [Etgar giggles]. But I think that the whole idea about books is that books for me are very much like human beings, and reading a book is kind of developing a friendship. So I think that, that kind of the trying to impose that everybody will have to befriend the same guy is something that just doesn’t make much sense. I think that really what literature has to give to us is this kind of variety and difference.

I have an anecdote about books! So I sometimes have meetings with troubled youth. And when I come you know I have to introduce myself, and I say I’m a writer, I write books.

And in one of those meetings there was a guy and he says to me, “so if you write books, you know, then I don’t give a fuck about what you say because it’s not interesting at all.” And I said to “amm… why?” He said: “You know, because I don’t waste my time reading books, I only do practical stuff: so I do pushups, you know, I run a lot, I learn how to pick locks. I do all kinds of stuff that can help me. Reading books, you know some kind of bullshit thing about this guy who lived in Russia a century ago, you know… You just waste your time.” And I said to him, “you know, actually I think it’s really really pragmatic.” And he says… he said to me “in what sense?” And I said to him, “because when you read a book you really can see how other people see reality, and not only you, so… Let’s say if you read a book about a girl who falls in love with a guy, and you read it carefully, maybe you know what girls are looking for in guys, so maybe you can trick a girl into falling in love with you!” So the guy said to me: “ehhhh, this is bullshit,” and he left the room.

And I finished the lecture and after the lecture I had to go to the restroom so I went to the restroom, and on my way out I saw this guy kind of checking out a book; And he was checking it out like you are petting an unfriendly dog. But I saw like for the first time he was looking at it, and there was this kind of sense of triumph. Because I actually think that, you know, that the same we we go to the gym, then when we read a book we exercise the muscle of empathy, which is a muscle that we usually in everyday life, we do our best not to put into stress. You know, when we see a homeless guy on the street, we can give him a buck or not give him a buck, but the last thing we want to do is to actually try and feel how the world feels, you know, through his eyes. So this is really this kind of safe area where we can really observe emotions, and see how the world looks from another way, and it’s safe because the moment that we put the book down, you know, we’ll be back in our lives.

Mishy Harman (narration): Etgar Keret. His latest project ,“Tel Aviv Noir,” is a collection of short stories he edited along with Assaf Gavron, by Israeli authors you haven’t heard of – yet. It’s out in English this month.

For years now we’ve been hearing the story of the revival of Yiddish. About it kind of finding this cool, almost-hipster, new life aside from being just the lingua franca of the Hassidic world. This is not that story. In America, sure: you’ve got Yiddish summer camps, Yiddish literature departments, Yiddish festivals, Yiddish punk bands, Yiddish podcasts, best selling Yiddish phrase books, even Yiddish organic farms. In Israel the situation is quite different. Step out of Bnei Brak or Me’a Shearim, and you’re basically as likely to hear Yiddish as you are to hear… I don’t know, Urdu. I mean everyone knows oy vey zmir, a groise metziya and a few other phrases their grandparents used to say. But there’s almost nothing hip about Yiddish here. Or at least that was the case, till this one, rather unusual man, appeared on the scene. Danna Harman went to meet him in the magical Yiddish center he built in the most unlikely of places.

Mishy Harman (narration): You know, for years now we’ve been hearing the story of the revival of Yiddish. About it kind of finding this cool, almosthipster, new life aside from being just the lingua franca of the hassidic world. This is not that story. In America, sure: you’ve got Yiddish summer camps, Yiddish literature departments, Yiddish festivals, Yiddish punk bands, Yiddish podcasts, best selling Yiddish phrase books, even Yiddish organic farms. In Israel the situation is quite different. Step out of Bnei Brak or Me’a Shearim, and you’re basically as likely to hear Yiddish as you are to hear… I don’t know, Urdu. I mean everyone knows oy vey zmir, a groise metziya and a few other phrases their grandparents used to say. But there’s almost nothing hip about Yiddish here. Or at least that was the case, till this one, rather unusual man, appeared on the scene. Danna Harman, yup, she’s my sister, went to meet him in the magical Yiddish center he built in the most unlikely of places.

Danna Harman (narration): Past the vendors hawking cheap knapsacks, phone cards, bed sheets, plastic plants and greasy falafels, up the ramp beyond the STD clinic and the school for remedial driving, and around the corner from a FilipinaIsraeli matchmaking agency and a kindergarten for African migrants’ children is a dark corridor with an open door.

Welcome to Tel Aviv’s massive and much maligned central bus station, the so called ‘New Bus Station,’ or the “Tachana Hamerkazit Hachadasha” where hapless commuters shuffle alongside foreign workers, refugee seekers, drug addicts, prostitutes and homeless all riding up and down the escalators leading to abandoned floors, searching for the Egged company buses out of here.

Through that door at the very end of the dark corridor, and into this mix add one Belgian born orthodox yeshiva boy turned bohemian Israeli a Yiddish performer and book collector.

Mendy Cahan: Shulem Aliechem, [Here Mendy continues to speak in Yiddish, which goes down to an under]

Danna Harman (narration): That’s him, Mendy Cahan, who is speaking here in Yiddish. He’s a 48-year-old bachelor with bushy eyebrows, sparkly blue eyes, and a receding mane of gray hair, who, today, is sitting at his desk among a clutter of papers and unpaid bills, chain smoking rolled cigarettes. He looks for his lighter… and then for his mobile phone…and then… thinking of an even better plan, he starts looking for his glasses. He then gets up to put on an old tin kettle for mint tea, swaying ever so slightly back and forth as he chats, a leftover, perhaps I think to myself, from his early Antwerp yeshiva days. (pause) Though you wouldn’t know it from looking at him, Mendy’s kind of a rockstar in the Yiddish world.

Mendy Cahan: I was born in Belgium, I grew up in Antwerp which is like really like a cosmopolitan Jewish city, I grew up with Yiddish, with French, Dutch and of course also Hebrew, you know. Like at school we learned the Mishnah, the Talmud in Hebrew. Like it was a traditional religious society, but opened minded at the same time. Like we also went to the synagogue and we also saw movies. At home we had books of Sartre, and Camus of my mother and we also had a good Jewish library with the Talmud, the Mishnah, the Marshut all kinds of exegesis.

Danna Harman (narration): In 1980, right after high school, he came to study in a yeshiva in Israel—but soon began straying from his Orthodox path, enrolling in secular courses at Jerusalem’s Hebrew University.

Mendy Cahan: From quite early on felt that I wanted to get out of the religious world, which felt to me like the small shtetl, everyone knew each other. I wanted to be in the universal world. Israel was for me an encounter with freedom, with sunshine, with open skies. I went to Hebrew University to study French literature, comparative literature, also physics and psychology and politics, whatever I could study, but what was funny is that the more I studied postmodernism like reading Barthes and Derrida, and Nouveau Ramaunt, suddenly it came back to be the whole structure of the Talmud, which was like an ideal in the eyes of Derrida, of this polyphonic voices and so, so it was funny to see, here I come and I want to get get away from the ‘altezachen’ as they say and I then I see that really all this, its not really altezachen, this is like the grose metziya, the gesheft you know.

Danna Harman (narration): On a whim, he decided to tack on a Yiddish literature class to his course load, just, really, for old times’ sake. And that’s when he realized something in Israel was amiss.

Mendy Cahan: It was really… like we were in the department we were three or four students, like really a small department, and the feeling was that it’s dying and here we are studying at a university, to keep the memory going but actually it’s a dying thing. And this feeling that it’s dying and that it has gone from the world and that it is not really much to say anymore, this was really disturbing. I lifted my eyes from the book and I said to myself hmmm.. Here we are in Israel, in our home country, finally, and where is all this like where where how come there is no even a memory of it? And I understood that these are my roots and I have to do something with it. And so I said to myself, “I am young, I have ambition, I want to do something interesting. I want to do something connected to myself creative, and so let’s take this Yiddish thing and let’s take a step further, let’s take it in to life.” Then I started to collect Yiddish books.

Danna Harman (narration): Mendy started collecting in 1996, putting out word that he would take care of any Yiddish book dropped off at his place in Jerusalem. He soon was overwhelmed… by calls and then visits typically from younger Israelis, who couldn’t speak Yiddish, and who, following the death of an older relative, didn’t know what to do with books left behind. Many of these youngsters, says Mendy, felt it would be terribly disrespectful to toss out their grandparents or parents’ libraries, and yet, also didn’t really want them there on their new IKEA shelves. Now they had a much better option, guiltfree, they could schlep them all over to Mendy’s and leave them on his doorstep. The piles in his living room grew and grew and grew.

Mendy Cahan: I didn’t know what I was going in to. Like I thought I would collect a few hundred, thousands of books, I will have a nice library and I will I will have good reading material.

Danna Harman (narration): Before World War II, there were some 15 million people in Eastern Europe who spoke and read Yiddish a mix of German, Hebrew, and Aramaic written in Hebrew characters. That world was lost and destroyed in the Holocaust.

But there’s been something of a mini revival of interest in Yiddish language and literature. Here in Israel, there are about 500 high-school students sitting for the Yiddish matriculation exams, there are more universities and colleges offering Yiddish literature as part of their courses and the Yiddish theater, which was founded in 1987, is venturing out of the retirement homes to entertain a slightly broader audience. But still, outside of ultraorthodox circles, in Israel, Yiddish basically is a dead language.

It never stood a chance really. In prestate Palestine and then later in newborn Israel, Yiddish was seen by many as a competition to Hebrew, the ancient biblical language which had been revived by Eliezer Ben-Yehuda and so Yiddish was not only neglected it was actually derided. When we spoke to Avshalom Kor, Israel’s go-to authority on the Hebrew language he explained that the attitude was….

Avshalom Kor: When you talk Yiddish, you are attached to the Diaspora, Eliezer Ben-Yehuda for instance, he was ready to talk to everybody in every language in the world, he knew many languages, but never Yiddish, because Yiddish is the concept, that you do not belong to the land of Israel. You do not belong to the language of the Bible.

Danna Harman (narration): That’s the anthem of the ‘Hebrew Language Brigade’ a group completely devoted to safeguarding Hebrew from foreign intruders, like Yiddish. “Speak Hebrew, Jew!” go the lyrics, “‘cuz that’s the language of your land and people.”

Avshalom Kor: There is a story about the riots of the years 36 until 39, riots against Jews in the Promised Land.

Danna Harman (narration): These riots are known today as ‘The Arab Revolt.’ ‘The Arab Revolt’ was a nationalist uprising by Palestinian Arabs against the British Mandate and the mass Jewish emigration.

Avshalom Kor: A Jewish bus on its way, Arabs started shooting. One of the Jewish passengers shouted יורים עלינו, כולם לשכב! ”They’re shooting at us, everybody lie down.” One of his friends stood up and said: “Dosh yistmen, un eret hebreish?!” It was Yiddish ‘Here they are shooting, and he talks Hebrew?!’ At the middle of the riots in the Jewish bus, there was the battle between Hebrew and Yiddish.

Danna Harman (narration): And indeed, in the 1930s and 40s, in an era that celebrated the figure of the tzabar, the strong, virile, tanned Israeli toiling away on the lands of a Kibbutz, Yiddish was losing that battle big time. Yiddish movies were boycotted, kiosks selling Yiddish papers were attacked, and local Yiddish musicians were banned from performing. All those Yiddish books saved from Eastern Europe and lovingly brought to the new land of the Jews, lay yellowing on dusty shelves. In a country that was trying to forget the Holocaust, they represented something weak, even shameful.

Mendy Cahan: I remember this woman, when I met her she was in like beyond her 80s, and she told me how she came here to Israel and with this whole feeling of wanting to give, she came from Vilna after the destruction and wanting to educate the children. And, and she says, and here I arrived and the first thing that she saw is that she started to talk to the children in Yiddish and they immediately, they were 3-4 years old, and they were putting their hands on their ears so they shouldn’t hear like they had this already inborn reaction to Yiddish and this hurt her so much, she said how did they know to close their ears? Like little children? Innocent little children, how did they know this? And this pain, when she told me, was as if it was fresh and alive and she told me like “My husband when he died he told me, it cannot be that they will continue seeing Yiddish like this, at some point it will change. And here you have arrived to take the books.” And so i felt like a calling.

Danna Harman (narration): Soon, Mendy’s little Jerusalem apartment was overflowing with donated books – and so he decided to make it all official and call it a library, a cultural center even, where these books could live on. He called it Yung Yiddish.

Mendy Cahan: Yung Yiddish. Yung means young in Yiddish so it’s to relate to the young energy to the rejuvenating energy of Yiddish, like if you have yin and yang, so you also should have yung.

At the beginning it was really like hushhush. People told it to each other from word of mouth. People came from BneiBrak, cantors, yeshiva students or people who like literature, who know how to sing, and suddenly young people who like to do exotic, strange, anarchistic things, and they were also of course, Yiddish writers, like Karpinovich, Yossel Birstein, and actors like Leah Shlanger, Michael Vineapple, like journalists. So there was a whole old gvardia who were also looking for for a stage to transmit this knowledge to the younger generation and to their own people.

Danna Harman (narration): The center was thriving, but Mendy was a bit uff shpilkes, as they say, and with the sunny beaches of the Mediterranean calling, he decided to get on route number 1 and head 45 minutes west to the big city of Tel Aviv. He set up shop, temporarily, in the basement of an office building, but when the space was taken over by a kindergarten a few years later, he found himself, together with oh, about 20,000 books and counting, evicted, and out on the street.

Mendy Cahane: Yeah, when you are a refugee you know with books or with pekalech, you don’t have much time to think. Every day is like survival. Like a Jewish survivors, not like the survivor of television you know.

Danna Harman (narration): Desperate, he followed a tip from friends of friends which led him to the behemoth bus station. There, as luck would have it, in something of an attempt to revive the reviled space, the city was offering cheap rents to encourage artists to move in.

Mendy Cahane: So I saw this place it was like a deserted parking lot, with birds flying around and no windows and nothing, no electricity, I had like 7 tons of Yiddish books, that I needed to find a house for, and so I said, “that’s it. that’s the place.”

Danna Harman (narration): He fixed the windows, swept the floor, brought in some second hand Persian rugs, and moved in with his horde of Yiddish treasure. If you go to Mendy’s kingdom today there are some 40,000 books there. It’s amazing! Periodicals and magazines fill the cavernous space behind the office they’re lined up on shelves, propped up against the walls, and piled high on the ground. Health magazines from Warsaw circa 1924, joke books out of 1930s Vilnius and beautifully illustrated children’s books from New York’s 1940s. There are novels by Shloyme Ettinger and Chaim Grade, poems by Mani Leib, plays by Yud Lamed Peretz, and translations of everything from Pushkin to Hemingway and Cervantes — all in Yiddish. Stop by. You won’t be alone. On any given day, besides Mendy and the occasional volunteer cataloguing books, or organizing a temporary exhibition, you are as likely as not to find, oh, maybe a few bearded hassids in the corner who have popped in to schmooze or a handful of Russian immigrants reading der Tunkeler or looking something up in an Avrom Reyzen poem. There are the occasional curious tourists who wander in, or shy students, who don’t know a schlemiel from a shlemazel but who might show up with a letter from a grandparent they have found and need translated, and then there are the young hipsters, lounging around, having a smoke with Mendy.

Mendy Cahane: Yiddish has become like really a fringe culture. It does not have a home, it does not have a nation, it does not have an establishment, so many groups who also feel that they’re not part of the establishment, at the fringes of society, they connect with Yiddish. So be it lesbians or homosexuals or people who don’t feel at home with this Hebrew militarism, they find Yiddish a more peaceful and a more lenient culture to connect to.

Danna Harman (narration): Several times a month, Yiddish fans of all sorts gather here for themed evenings: everything from singalongs to cabarets to Holocaust memorials to herring and kugel tastings. Mendy will typically get up on the stage at some point, often with a visiting artist in tow, and, with the always appreciative crowd swaying and humming along, he will begin to croon. [Tape comes up with Mendy singing, goes back to under]

This evening he has invited his keyboard player, a small lady in her 70s, to center stage. She takes the microphone, flashes a sort of flirtatious smile, pushes back her gray hair, strikes a pose and channels Edith Piaff in Yiddish, of course. The crowd, to use a Yiddish word my mom taught me, kvells. At the end of the evening, we sit around near the oversized cushions depicting the greats of Yiddish literature Mendele Mocher Sforim, Shulem Aleichem, and Yud Lamed Peretz – and we talk. Mendy pours out the ‘mashke,’ the vodka, for a bissel l’chaim, he says, and rolls himself another cigarette. The buses rumble overhead, shaking the entire room, and a muffled announcement in Hebrew informs us that the 394 will soon be leaving for the city of Elat. And then it’s quiet for a moment, allowing my thoughts to wander. What would all the great Yiddish writers and thinkers make of this central bus station library? I ask Mendy. How would they feel about the home provided to them in the Land of Israel?

Mendy Cahane: Well… don’t know if they will dance from joy, because on the one hand there were millions of readers around them, and here these books are a little bit hmm… left aside, a little bit hurt. But there are so many intelligent bright things and so much work in this books, so much thoughts, if I would have some money I would make panels, so that you can see the writers, their biographies, and then you could see the richness of all this, but for the moment, this is the best we could do so, that’s it, but I believe it will grow, it will.

Mishy Harman (narration): Danna Harman. Danna’s a journalist who has written from all around the world. For the past few years she’s on staff at Ha’aretz, where she also writes a column of love stories. And, speaking of which… About half an hour southeast of Be’er Sheva, basically in the middle of nowhere, there’s a small town. Dimona. [enter music?]. Around the world it’s best known for what Israel denies is there our national nuclear plant. And honestly, that’s more or less what it is for most Israelis too: A quick pit stop on the way to Eilat. You get out of the car, refuel, go to the bathroom, crack a lame joke about radiation, and keep on driving into the desert. [beat]. Dimona was originally built in the 50’s as what was known then as an עיירת פיתוח, a dumping ground for waves of immigrants from North Africa. It’s a very well known saga, but the leaders of מפא״י, the ruling labor party, essentially tricked these new immigrants into believing that they were being housed in a central location, with lush surrounding. That it was a ten minute bus ride from Haifa and the beach. But reality was bleak: Poverty, unemployment, crazy heat, and nothing but sand and sand and sand. Almost all the people still around from that generation are super bitter. Whoever could, left.

About half an hour southeast of Be’er Sheva, basically in the middle of nowhere, there’s a small town called Dimona. Around the world it’s best known for what Israel denies is there – our national nuclear plant. And honestly, that’s more or less what it is for most Israelis too: A quick pit stop on the way to Eilat. You get out of the car, refuel, go to the bathroom, crack a lame joke about radiation, and keep on driving into the desert. Dimona was originally built in the 50’s as a dumping ground for waves of immigrants from North Africa. It’s a very well known saga, but the leaders of מפא״י, the ruling labor party, essentially tricked these new immigrants into believing that they were being housed in a central location, with lush surrounding. That it was a ten minute bus ride from Haifa and the beach. But reality was bleak: Poverty, unemployment, crazy heat, and nothing but sand and sand and sand. Almost all the people still around from that generation are bitter. Whoever could, left. But for Chaya Gilboa, a thirty-one year old with a huge mane of flaming red curls, Dimona is something completely different. It’s where she first encountered the book which – she believed – would change her life – the ‘Book of the Yellow Pears,’ by a relatively forgotten author, Pinchas Sadeh. Dana Ruttenberg reads this story.

Mishy Harman (narration): But for Chaya Gilboa, a thirty-one-year-old with a huge mane of flaming red curls, Dimona is something completely different. It’s where she first encountered the book which she believed would change her life. That book, by the way, is called ספר האגסים הצהובים, the ‘Book of the Yellow Pairs,’ and it’s by a relatively forgotten author, Pinchas Sadeh. But before we hear Chaya, here’s a little excerpt from that book:

“When I was twenty-two years old,” Sadeh wrote about himself, “I stepped out of my room in Jerusalem in order to tour the country. I travelled through many places and eventually, one autumn afternoon, reached Tel Aviv. I wanted to rest for a moment and as I could think of no better place I walked into ‘Beit Bialik’ the former home of Israel’s national poet Hayim Nahman Bialik. At the entrance I was greeted by the librarian, who already then seemed to me a very old man. He asked me what book I was looking for. Since I wasn’t really interested in any one book in particular, I randomly mentioned the name of my first and only book at the time. The librarian asked for the author’s name, and, slightly embarrassed, I replied. Then he said, and this was his last and decisive statement to me: ״We have no such book! There is no such book! There is no Pinchas Sadeh.”

Chaya Gilboa: It all began in Dimona, which is basically the last place I thought anything could ever start. I was in the middle of my second year as a Talmud major at Ben Gurion University in Be’er Sheva, and I’d fallen head over heals for this guy, a percussionist, from Dimona. I was so desperate for his attention, that I began roaming around, kind of aimlessly, in his sleepy town, hoping to bump into him. But just in case that happened, I needed a good excuse.

In the end, I found the perfect one: A local oud teacher agreed to give me some lessons on an instrument that I had never before touched, and frankly, had no real desire to master. So… There I was, in Dimona, twice a week, Tuesdays and Thursdays, making sure I arrived early enough to wander the streets, hoping to meet my guy. On one particularly sweltering mid-July Thursday, I ducked into the municipal library for some shade.

The elderly librarian looked up and gave me a suspicious glare as she slowly dragged a cart full of books behind her.

A few kids sat on puffy pillows in the corner and listened quietly as a volunteer read to them from Edmondo De Amicis’ Heart.

I picked up a random book that was laying around on one of the tables. Pinchas Sadeh’s Sefer Ha’Agasim Ha’Tzehubim The Book of the Yellow Pairs. I vaguely recalled the author’s name. In high school, if I remembered correctly, we were forced to read another of his books, Life as a Parable, for our final matriculation exam.

After flipping through its pages for a few minutes, I made sure the librarian wasn’t looking, slipped the book into my bag, and walked out of the library. When I think back on it today, I actually have no idea why I stole that book instead of just borrowing it. I guess I was so nervous about the guy, that I didn’t want to leave any traces of ever having been there.

A week later I finally mustered enough courage and called my guy. We sort of dated for a few weeks, till he decided I wasn’t his type, and that was that. The library, the unbearable heat, and my oud teacher, all stayed in Dimona, while I returned to my Talmud books and student life in Be’er Sheva.

A year passed, and Yom Kippur came around. I was home in Jerusalem, but didn’t want to spend the holiday in the Ultra-Orthodox neighborhood where I had grown up, and where my family still lived. For once, I wanted an uplifting, spiritual alternative; one that wasn’t comprised of long hours staring at the pages of a prayer book in the crowded ladies’ section of the local synagogue.

So I asked a friend if he would spend a quiet day with me at a small natural spring in the hills of Jerusalem. When he honked from downstairs, I quickly threw some clothes into a bag, surveyed the bookshelf, and without much thought grabbed a smallish book with that cheap plastic cover old libraries use, and ran for the door.

OK, this might be a good time for a confession: I like to exaggerate and romanticize. A lot, actually. But this, I promise you, is not one of those times.

Here’s the plain truth: Pinchas Sadeh’s Book of the Yellow Pairs was, hands down, the most beautiful and wild text I’d ever read. I’ve reread it many times since, but the impression it made on me that very first time, while I was dangling my feet in the cold water of the spring in Even Sapir, on the Yom Kippur before my last year at the university, will never really fade. His sad short stories wormed their way into my heart, and tinkered with my breath. It’s such a cliche, but I couldn’t put it down for a second. When I reached the last page, I suddenly had this rare moment of total clarity. An epiphany, I guess: My future love, my life partner, the one I was always looking for, would somehow be connected to this book.

I turned to the inside back cover, and pulled out the borrowing card that little index card in which stern looking librarians used to write down the name, address and telephone number of the borrowers, you know, in the era before books started being checked out like items at the supermarket. There were five names: Three men and two women. Now, I know this sounds crazy, but at that moment, as the sun was setting and Yom Kippur was ending, I was just certain that my bashert, the father of my future children, was on that list.

That night, I broke the fast with an old friend. I told him about my plan to call each of the three men on the card and insist that they meet me. “That’s the craziest thing I’ve ever heard,” he said. “If someone called me with that story, I’d immediately call the police and tell them an insane woman had stolen a book from the Dimona public library and was now stalking me!”

But I didn’t care. I knew that my romantic fate was inscribed on the library card of the most beautiful book that had ever been written.

Years later I still try to understand what exactly made me impose my wild fantasy on someone I hadn’t even met? As if love wasn’t something that happened naturally between two people, but instead required some third, external, entity, to form the bond.

I waited for two days before calling the first guy on the list: Udi. Doing my very best to sound extra nice, extra sane, I asked for a minute of his time. I then told him about the book, and how I felt that there was some special bond between all those who had read it. Udi sounded kind of stunned by the whole thing, and was a bit too quick to point out that he had no recollection of borrowing the book from the Dimona library, or, for that matter, of ever reading it. After a few seconds of what was a very awkward silence, he suddenly remembered. A few years ago, he told me, he had taken it out for a friend who needed it for a seminar paper he was writing. This disappointing answer caught me off guard. I had liked Udi’s voice from the moment he had picked up the phone. “Do you want his number?” Udi asked. I debated whether this was within the rules of my fantasy. Sure, it was a once-removed-connection, but still, it felt kosher. I hesitated for a second, and said yes.

With the friend it was much easier: He was from Be’er Sheva, remembered the book well and was happy to meet up. But something in the conversation, maybe it was his tone or cadence, seemed a bit off. Still, I was on a mission, and I wasn’t going to let any vague feelings stop me.

We met at a bar not far from the university. My heart was racing when we shook hands. I looked up at him melodramatically and explained the whole thing in one breath. He seemed completely bewildered, trying to grasp the fast stream of words spilling out of my mouth. When I finally stopped to inhale, he smiled. “I get it,” he said. “It’s such a charming story, and you seem so sweet, but I gotta tell you that I don’t exactly fit the role you’ve cut out for me. I live with my boyfriend, you see, so…”

It took me a few moments to recover. I let him pay for my beer, and went home to strike his name off the list. But honestly, my inner screenwriter was secretly pleased. Every good tale needs a few twists, and this-I convinced myself- was just a mandatory first plot point.

I took a deep breath, picked up the phone and dialed potential-lover-number-two: Natan. I had to leave him several voice messages before he finally called me back. After quietly listening to me for while, he began interrogating me: who was I? What had I been doing in Dimona? Was I interested in meeting him for a research project?!?! He adamantly refused to meet in Be’er Sheva, or really anywhere outside of Dimona. So I went to meet him.

In the car on the way there I thought to myself that I love the name Natan. Sure, the immediate association is with Sharansky, the famous cap-wearingrefusnik-turned-hawkish-politician, but still… The name has such a crisp and warm sound to it. It’s a lover’s name. A companion. Someone to grow old with. My ride dropped me off at the entrance to town, and I walked towards its small, dusty, center.

Natan recognized me at once, based on the description I had given him on the phone. (I guess not that many curly redheads show up looking lost in central Dimona). He waved with a friendly hello. He was sitting on a plastic chair outside a kiosk, balancing a cup of black coffee on his knee. He had brown eyes, thick black hair and one dimple on his left cheek. Sweet-looking, but… just about my father’s age.

As I waited for the bus back to Be’er Sheva, I started to wonder about this whole escapade. Was I was forging ahead out of a true conviction that my beloved was on that old library card, or had I just fallen in love with my story, with the romanticism of the search?

Before I could answer that question definitively, there was one last name on the card. My final shot. “God,” I looked up and pleaded, “be kind.” I didn’t want to believe that I had been wrong. That the library card wasn’t my secret map to love.

Shalom was the third on the list. It took me a few days to get through to him, because the last two digits of his phone number on the card were smudged. I patiently tried every possible combination until I reached him. Maybe it was my perseverance, or just luck, but Shalom ‘got me’ immediately. Everything seemed to fit. I checked this time: He was my age, straight, had a soft voice, and remembered the book. His dad lived in Dimona, but he was now studying social work at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. I got on the 470 bus with quite a bit of excitement. I brought the book with me, and he got a kick out of that. He had these big comforting eyes, and didn’t think I was crazy at all. I liked him. Then he told me that he actually didn’t enjoy the book all that much, and had borrowed it by mistake, thinking it was a different Pinchas Sadeh novel. Was this enough to call the whole thing off? To declare the voyage for my literary soulmate an utter failure? After all, I had set out believing that whoever loved this book as much as I had, would also have to love me; that it was enough for two strangers to share a love for a third thing in order to bind them together forever. So now what?

Shalom didn’t care for the book, but he liked the story I had created around the book. At least that’s what he told me. He walked me to the station to catch the bus back to Be’er Sheva. But before we parted he touched my cheek so naturally that my heart kind of quivered. So I didn’t get on the first bus that came, or the second. I stayed in Jerusalem that night, and dove head first into an intense love affair.

As much as I would like to stop right here, I can’t. The story has a different ending: After two months, Shalom broke up with me. Honestly, I can’t really blame him. I don’t even know how he stuck around that long. When he ended it, he told me that he felt like I was more enchanted by the idea of who he could be than who he really was. I knew he was right. I mean nothing gave me more satisfaction than knowing that my crazy odyssey had panned out; than telling people how we met, and seeing the jealous faces as we unfolded the tale of our improbable romance. But if I’m being honest with myself, there wasn’t much more than that. We went our separate ways, and I haven’t seen him since.

And the stolen copy of The Book of the Yellow Pairs? I hid it behind a row of cookbooks on my shelf, and swore never to read it again.

That didn’t last. I’ve returned to it since. Dozens of times. In search of secret clues hiding behind Sadeh’s words. Hoping that somehow they’ll point me towards my guy, who like me, understands.

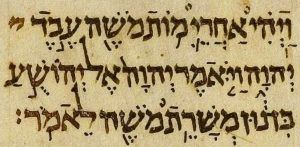

There’s one book, an ancient one, more than a thousand years old, which stands at the center of one of the most fascinating mysteries in Jewish history. Over the centuries, this book was concealed, venerated, pillaged, salvaged, smuggled, made to disappear, and miraculously appear once more. That book is the Aleppo Codex. Today, part of it is displayed as a national treasure in Jerusalem, and part of it is a kind of Holy Grail sought worldwide by professors, rabbis, spies and collectors. Together, these people, enthralled by the magic of this codex and its story, make up a sort of underground society. For them, this book is much more than just a book. Matti Friedman encountered them completely by chance.

Matti Friedman: It was the summer of 2008, I was a reporter here in Jerusalem and I was kept busy covering the endless routine of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, but I was desperate to write about something else, about anything else. One day I was at the shrine of the book in Jerusalem, at Israel’s national museum, which is where the dead sea scrolls are kept. Everyone knows the dead sea scrolls, they’re celebrities, they’re the Beyonce of ancient Hebrew manuscripts. The scrolls gallery was full of tourists who were looking at these 2000 year old fragments of parchment. A flight of stairs led down from that gallery into a dark room. It was essentially a basement and it was empty. And there I encountered another book. And from the labels I understood that this was the singular perfect copy of the Hebrew bible, probably Judaism’s most important manuscript. It was one of the most important and valuable books on Earth but I had never heard of it. That gap between its importance and its anonymity seemed to me to be worth exploring.

Mishy Harman (narration): Adolfo Roitman is the museum curator in charge of the codex.

Adolfo Roitman: The majority of the Aleppo codex is this manuscript is the most significant traditional version of the Hebrew bible. You know, it’s a kind of metaphor of the presence of God on Earth, is the word of God– and the book itself was revered by Jews for centuries. Seeing this book as the real presence of God.

Mishy Harman (narration): So what does being the perfect version of the Hebrew bible even mean?

Matti Friedman: Take a religious institution like the Catholic Church for example. The church is held together by a central office which is called the Vatican, and it’s in Rome, and it sets doctrine and appoints clergy and it runs the church. But Judaism never had anything like that, and after the destruction of the temple of Jerusalem in 70 AD and the beginning of the exile, there was very little holding these diaspora communities together. For people dispersion had always meant extinction and if the Jews were going to be an exception, and they very much wanted to be an exception, they needed a mechanism that would allow them to somehow stay one people even though they were now speaking different languages and they were answering to different kings. And the mechanism needed to be portable because they were now moving around the world and what they came up with was the idea that a people would be held together by words. They would have a book that they would all read. This book is the collection of texts that we know as the Hebrew bible. But the mechanism only works if they’re all reading exactly the same book because any variations would lead to fragmentation, to religious schisms. So you need an agreed upon master copy, a kind of atomic clock of Judaism. And that is the Aleppo codex, the authoritative version of the bible.

Mishy Harman (narration): The codex was written about 930 AD on the shores of the Sea of Galilee. After that, it was moved to Jerusalem, seized by the soldiers of the First Crusade, and then ransomed by the Jews of Cairo. In Cairo, it was actually the personal bible used by the great Jewish philosopher and physician, Moses Maimonides. A few generations later, it traveled from Cairo north to Aleppo, a trading center in Syria, where it became the treasured possession of the city’s Jewish community. It remained there hidden in the Great Synagogue in a safe with two locks for 600 years. Lena Sutton, who lives in Israel and is now in her 80s, still remembers the mystique around the Codex.

Lena Sutton: During the holidays or on special occasions like bar mitzvahs, they would take the Codex on its Corrado and parade it among the congregants and everyone lined up to kiss it because it had power. If a woman was trying to get pregnant she’d get close and touch it. Anyone with the special request would come near.

Mishy Harman (narration): The Jews of Aleppo came to believe that the book protected their community. It was their talisman. Here’s Lina’s husband Rafi also from Aleppo.

Rafi Sutton: Many legends and beliefs got tied up with the book. If it were ever moved, if it ever left Aleppo, a horrible plague would strike the community. Leprosy or even worse. Destruction. All kinds of dark things.

Mishy Harman (narration): So this all sounds kind of dramatic, but it’s pretty close to what ended up happening. Today, there are no Jews left in Aleppo. It’s the largest city in Syria, a major battlefield between Assad’s government and the rebel forces. And it makes you wonder what would have happened if the Codex were still there. Books, after all, don’t fare well in wars.

On November 29, 1947, the United Nations voted on the partition of the British mandate in Palestine into two states: one for the Arabs and one for the Jews. The next day, riots erupted in Aleppo. A mob burned Jewish homes and businesses, and also the Great Synagogue where the Codex was kept. The book disappeared, and most people thought that it was lost for good. But ten years later, Matti explains, it resurfaced in mysterious circumstances– this time in Jerusalem, in the new state of Israel.

Matti Friedman: It turned out that the Codex actually survived. It had been hidden first by a Christian merchant and then by a Jewish merchant in the old Aleppo bazaar before it was smuggled out of Syria by a Jewish family who hid it in their washing machine. It reached Turkey and then it traveled by sea to Haifa which is an Israeli port. And from there to Jerusalem in early 1958. It ended up in an important academic institute called the Ben Tzvi Institute which was founded by Israel’s second president, Itzhak Ben Tzvi, who was also a scholar and I guess you could say an early member of the Aleppo Codex underground. He had been obsessed with the book since the 1930s and he had done everything in his power to bring it to Jerusalem, including a failed attempt a few years earlier to use the Mossad to smuggle it out of Syria. Now in 1958 he finally got his wish, he had the book. When the Codex arrived in Jerusalem, two questions arose. One was–who owned Judaism’s greatest book? Was it the community that had cherished it and cared for it for 600 years or was it the new state of Israel? That question became the subject of a fascinating legal battle that was fought in a court in Jerusalem over four years. But the second question is the one that preoccupies The Aleppo Codex underground to this day. When the book was written more than a thousand years earlier it had about 500 pages. But when it turned up in Jerusalem it had only 294 pages. So about 40 percent was missing and the pages that were gone weren’t just any pages. They included the Torah, the Five Books of Moses– which is the most important part of any Hebrew Bible manuscript. And there are other books missing as well, like Daniel, Esther, and a few others.

Mishy Harman: So what did people think had happened?

Matti Friedman: Well the accepted belief was that the pages had been lost in the fire in the Great Synagogue in 1947. The physical appearance of the codex seemed to support that idea because on the bottom outer corner of each page there is a purplish discoloration that looks like a burn mark. So for years people just assumed that that was what happened and it was convenient because if the pages had been burned you didn’t have to look for them. But in 1986 the book was sent for restoration and a manuscript expert took a close look at these burn marks, and he sent samples to a microbiology lab, and when the slides came back the expert told me he literally jumped out of his chair because the slides showed clearly that the purple marks weren’t burn marks. They were fungus, and in fact there was no evidence at all that the Codex had ever been damaged by fire.

Mishy Harman (narration): If they hadn’t been destroyed in a fire, where were the missing pages? They had immense value to collectors, to Aleppo exiles and to scholars, and because there are no known copies of photographs of the codex, the absence of the pages means that the original perfect texts of the Bible can’t be recreated. In the 1980s, two fragments surfaced: a page from the book of Chronicles, and a fragment from Exodus with a few passages describing the plague of frogs which God sent to afflict Pharaoh and the Egyptians. Both fragments were found in, of all places, Brooklyn, New York, where they were held by Aleppo Jews who had immigrated to the U.S. and who believed that the pages of the codex had the power to protect them against the evil eye. At first, researchers were really excited. They hoped that the discovery of these pages would lead to the rest of the missing pieces, but they never did. More than 200 pages remain missing. Since then, nothing else has ever turned up. The mystery continues, and that is where the Aleppo Codex underground comes in.

Matti Friedman: Early in my research I found myself sitting in the living room of an 80 year old ex-Mossad agent named Rafi Sutton. He was born in Aleppo and escaped to Israel as a teenager. He knew I was looking for information about the Aleppo codex and I knew that he had been investigating the story for years. So he puts an enormous file folder on his coffee table and then he looks at me. I was thrilled because for a reporter, a folder full of yellowing documents is like a juicy hamburger in front of a starving man. But it soon became clear to me that he had no intention of actually letting me see what was inside the folder. This was a guy whose profession was trading in information and secrets. He spent time abroad undercover. He had run agents in the Jordanian sector of Jerusalem in the 50s and spies like that don’t just give information away, and I think that was my first introduction to the underground. Another key figure is a guy named Ezra Kassin who’s in his 40s. He did his military service as a young man as a detective in the military police and later ran a center for the study of Kabbalah, of Jewish mysticism. And he can describe the Great Synagogue of Aleppo in meticulous detail.

Ezra Kassin: I turn left, go down a flight of stairs, and now I’m standing in front of the main gate of the synagogue, and I can already feel the sanctity, a sense of awe completely engulfing me. There’s like an inner trembling and excitement, a sense that I’m in the midst of heightened spiritual ecstasy. I push the really heavy huge wooden doors. The hinges creak, the door opens, and I enter. Now I find myself walking down a long corridor leading to a small grotto where the holy Codex is spending money. It’s the object of our prayer. The ancient and holy treasure of our community.

Matti Friedman: What’s amazing is that Ezra is describing a place that he has never seen. He was born in Israel years after the Codex arrived from Syria. His home is packed with binders of material on the Codex that he’s collected and his wife, who I also got to know over the years that I worked on this book, she knows that she has to share her home with Ezra as other true love. Ezra probably has more information on the Codex than anyone else alive. But as was the case with Rafi, the first time I met him I got nowhere. He would say things like, “You know Matti, one wrong word to someone in this story and ten other doors will slam shut.” And then he would kind of look at me with a sly grin and he wouldn’t say anything more.

Mishy Harman: So was this frustrating to you?

Matti Friedman: It was but it also tipped me off to the existence of a good story that was being concealed and after a few months of persistence the doors cracked open.

Mishy Harman (narration): Slowly, Matti gained more trust as he began to become a part of the underground himself. He learned that there were significant cracks in the official story.

Matti Friedman: Raffi Sutton, the retired spy, found an elderly rabbi from Aleppo who was by then living in Buenos Aires, and he turned out to be a very reliable witness. The rabbi told him explicitly on camera that he had seen the manuscript whole in 1952. That’s five years after the riot in Aleppo and the fire in the seminar which is when the pieces were supposed to have gone missing. But the rabbi said no, that was not what happened at all.

Mishy Harman (narration): What that meant was that the pages went missing sometime after the rabbi saw them, and there weren’t that many options. Either when the book was being guarded and hiding by the Jews of Aleppo or in transit through Turkey or — and this was the most explosive potential conclusion– after it reached Israel and was being held by the scholars of the president’s Institute.

Matti Friedman: One of my first questions was– when was the first time someone wrote down which pages were missing? And I thought this would be easy to find out. But of course like everything with the Codex turned out not to be. After spending a lot of time in archives I realized that no one had noted how much was missing or that the Torah was missing before March 1958, which is a decade after the fire and it’s after the Codex arrived in the hands of the president. I also started finding evidence that there were other valuable books missing from the collection at the same institute. The academics who are the custodians of the codex today and who I had at first saw as neutral observers who I could consult with about this very complicated story, they clammed up and eventually refused to cooperate or provide me with documents that I requested. Even when I filed a request under Israel’s Freedom of Information Act.

Mishy Harman: But why was that, Matti?

Matti Friedman: That will take a long time to answer. Their refusal of course made me more curious. And by this time I thought of myself as a member of the Aleppo Codex underground and I would meet Ezra or Rafi or some of the others and we would trade secrets and fragments of information.

Mishy Harman (narration): I asked Matti what he thinks it is about the Codex that sparks this kind of obsession. Jews have a long love affair with books. They aren’t known as the “people of the book” for nothing. Texts were the way Jews maintained their identity over centuries in the diaspora. And there has traditionally been a deep regard for words. For example, when a Torah scroll is taken out in a synagogue, the congregation stands up on their feet like you would stand up when a judge enters the courtroom. And the scrolls often are decorated with a silver crown as if they were some sort of royalty. But Matti actually thinks that there’s something even deeper going on here.

Matti Friedman: There’s a central idea in Jewish mysticism that the world was once whole and that it then shattered into many fragments, and the universe is broken and it needs to be put back together. And we do this by our good deeds, and the end of the process is is redemption. I love the idea that is taught by many mystical traditions over the centuries and millennia that that the journey is actually the point, the journey is as important as the destination. It’s not coincidence that Ezra Kassin of the Aleppo Codex underground is also a scholar of Kabbalah which is the mystic tradition because in this story you have the meeting of these two Jewish preoccupations– the desire to make things whole and the love for the written word. It’s an attempt to collect missing pieces. The pieces of book. And I think that the idea here consciously or not is that if we put the Aleppo Codex back together, we’ll actually be restoring something much much greater.

For help on today’s episode, thanks to Ethan Pransky, Jeremy Schreier, Ravit Sheffer, Julie Danan, Tomas Grana, Daniel Estrin, Nava Winkler, Norman Gililand, Paul Ruest, Mitra Kaboli, Tiffany Roberts, Lev Keret who generously volunteered his room, and of course to Goldie the geriatric goldfish, who passed away a day after this episode aired. May he rest in peace in fish heaven. As always to Charles Monroe-Kane, Caryl Owen, Steve Paulson, Anne Strainchamps and all the team at TTBOOK. Our executive producer is Julie Subrin and a huge thanks to the rest of the gang at Tablet. Israel Story is produced by Mishy Harman, Yochai Maital, Roee Gilron and Shai Satran.