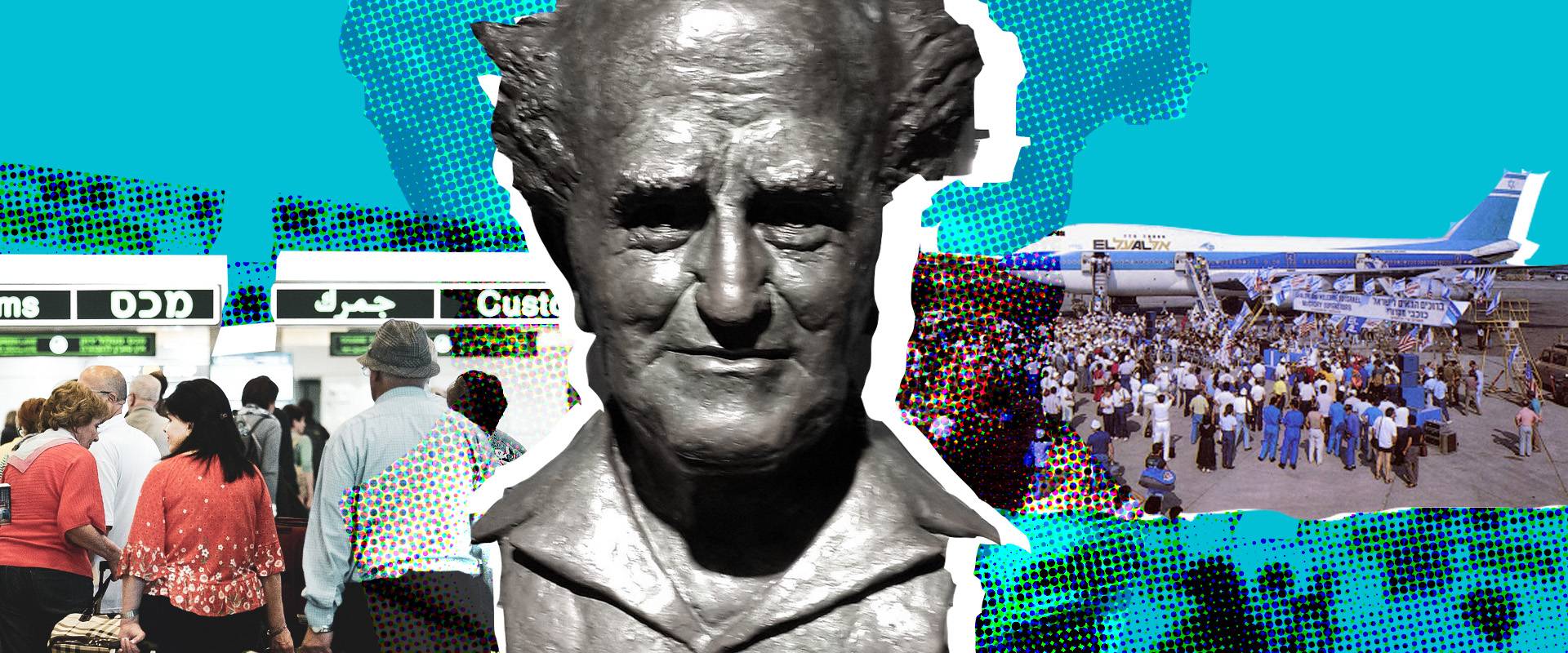

The first place travelers to Israel encounter is usually Ben Gurion Airport. What they’ll remember of that experience depends in part on their relationship to the country. Are they coming home? Arriving to a place they’ve always dreamed of visiting? Passing through, with fear or wariness, en route to someplace else?

In this week’s episode of Israel Story, we hear from people who have had unforgettable encounters in or on their way to TLV.

A grandmother gives a Hebrew lesson to a superstar.

Act TranscriptMishy Harman: Lily, can I ask you, how old are you?

Lily Sayegh: Ohhhh! Eh, more than eighty, nu! I born in Iraq.

Mishy Harman (narration): That’s Lily Sayegh, who came to Israel from Basra in 1951 when she was eighteen. Now she lives in Ness Ziyona, near Rehovot. She has nine grandchildren. Sixteen great grandchildren. In late September this year, Lily was coming back to Israel after visiting her son in the States.

Lily Sayegh: Beverly Hills, they live.

Mishy Harman (narration): The son drove her to LAX, she checked in.

Lily Sayegh: Actually, I… I have a ticket in the איך קוראים לזה, merchant department?

Mishy Harman: In the economy class!

Lily Sayegh: Yeah! yes.

Mishy Harman (narration): But, as I guess sometimes happens if you’re an elderly woman travelling on a long flight. She was upgraded.

Lily Sayegh: Yeah, they gave me a seat in the first class.

Mishy Harman (narration): This was Lily’s first time in first class. So she got on the plane, was shown to her seat, given a tall glass of champagne, a hot towel. And she said hi to the gentleman sitting next to her. He was good looking, in his late thirties, wearing sun glasses. His name:

Lily Sayegh: Ehhhhh… Ke… איך אומרים? West Kenye…Kenye, his name?

Mishy Harman: It was Kanye West!

Lily Sayegh: Kanye West, that’s it! That’s it.

Mishy Harman: Had you ever heard of Kanye West before?

Lily Sayegh: No! I am not the age. [Lily laughs]. Maybe my grandson, my grandchildren, my children, but not me.

Mishy Harman (narration): Kanye was on his way to Israel for a show, and Lily, she had some advice for him.

Lily Sayegh: I told him, “OK, when you go to the show, you speak Hebrew, I will teach you.” He say, “OK,” [Mishy laughs then Lily laughs], I told him: “You just tell them, Shalom, say shalom.” He say “shalom.” “I am very very glad to be with you, ani sameach.” “Ani sameach. ” When we reached the third word, “lihiyot itchem ,” here he stop. He say, “I can’t, I can’t say those words. This is very hard for me.”

Mishy Harman: So you gave Kanye West a Hebrew lesson?

Lily Sayegh: Yeah! [Lily laughs] You know. He is a very nice gentleman. He is a really gentleman, yes. He looks good. He is handsome. I wanted to speak with him more, but I smiled to him, he smile.

Mishy Harman: What happened when you landed in Ben Gurion?

Lily Sayegh: When we arrived they came and took him. He went he didn’t tell me bye. [Lily laughs].

Mishy Harman: So what do you think, Lily?

Lily Sayegh: Nice, very nice, very nice.

Mishy Harman: You like it?

Lily Sayegh: Yes!

Mishy Harman (narration): So just recently, I flew from Boston to LA., on what Todd, a Logan airport TSA officer, told me was one of the busiest days of the year.

Todd: Yeah, it’s going to be busy. I’m going to be here both Christmas and New Years.

Mishy Harman: Really?

Todd: Yeah!

Mishy Harman (narration): It was the Friday before Christmas, and all the Boston area students had just finished with finals, and were flying home for the break. I got there at like 4am for a 6:30 flight, and the lines were snaking all the way into the parking lot. Babies were crying, parents were exasperated, students were nervously checking their phones every two minutes. No one was having a good time. Not the TSA officers, who were trying to maintain some order, and definitely not the passengers, many of whom were yelling and screaming and complaining. And the whole time, I was thinking to myself, ‘you know? this feels familiar.’ There a few things that almost everyone who has visited Israel has in common: They’ve walked through Jerusalem’s Old City, they’ve floated on the Dead Sea, they’ve climbed Masada, and… they’ve had some sort of saga at Ben Gurion Airport. For a lot of people including me landing there is an emotional experience, a homecoming. I remember passengers used to sing Hevenu Shalom Alechem and clap and cry, as soon as the plane landed. But for others, the reception is more complicated: If you’re Arab, if you look Arab, if you’ve visited an Arab country, prepare yourself for an endless stream of questions. But even if you haven’t, or you’re not, it’s not always smoothsailing. Tourists are often asked if they’re Jewish, and if they went to Sunday School, or keep kosher, or know what’s on the Passover plate. Not long ago my sister Danna came back home to Israel and stood behind a Chassid in line for passport control. He had a black hat, black coat, long earlocks, straight out of central casting. The guy was so religious he could barely make eye contact with the young female officer who was questioning him. But she just looked right at him and said “So Moshe Menachem, you are Jew?!” Israeli airport security is really tight, and it’s a huge issue, that gets a lot of people both Israelis and foreigners riled up.

Israeli airport security is really tight, and it’s a huge issue, that gets a lot of people – both Israelis and foreigners – riled up. That brings us to our first story today. The story of Nathan and Emily. Act One – “Think Very Very Carefully.”

Mishy Harman (narration): Nathan Filer and Emily Parker from Bristol, in the UK, had been going out for just over two years, when, in April 2012, they flew into Ben Gurion airport. This was their second time there.

Emily Parker: And the flight was smooth…

Nathan Filer: I don’t remember it, so I’m guessing it was smooth, yeah I’ve got no memory of the flight at all.

Emily Parker: We were quite nervous when we landed.

Nathan Filer: Yeah.

Emily Parker: Suddenly.

Nathan Filer: So you go through… It’s a nice airport, isn’t it? It’s very modern and there’s some sort of big round atrium or something that we went through, and then got to the passport booths. And then the rapid questions start.

And…

Emily Parker: We were asked the purpose of our visits.

Nathan Filer: What’s your father’s name

Emily Parker: And had we been before.

Nathan Filer: What’s your father’s father’s name?

Mishy Harman (narration): That’s when things started to get complicated. They were taken into a side room, for further questioning.

Nathan Filer: A couple of hours went by with us there together. And it’s during this time that they would ask us for some information about ourselves. So they wanted our names, they wanted phone numbers, they wanted our contacts at home, they wanted our emails, and they wanted our email passwords.

Mishy Harman: Did you guys talk amongst yourselves as to whether you wanted to give them your password? Emily Parker: Yeah, we felt like that if we didn’t we definitely not be able to get through the airport, because that would be enough for them to say, “well, you’re hiding something.” But obviously it’s a massively personal… You know, we didn’t feel we were guilty of anything, or… So it wasn’t like we had anything wrong to hide, or…

Nathan Filer: So you’re sort of doing the baffled tourist, and I mean my stomach was just turning. You know, I’ve got a lot of respect for authority figures. I’m not a kind of natural rebel, really [Nathan laughs]. Like someone in a uniform or whatever, and I “oh, I wonder what… I should definitely do what they say,” you know, so it kind of goes against the grain, you know I’m not proud to admit that, but when they asked for our email passwords we weren’t going to give those over, because I hadn’t deleted… If they did go into my email and they typed ISM or Palestine or you know anything at all, there would just be, you know it’s Gmail every email you’ve ever sent is there, isn’t it? And we hadn’t gone through and done anything about that, so we were… I was never going to hand that over and that meant straight away we were in conflict with them, because straight away they were then suspicious.

Mishy Harman (narration): If the security folks had gone through Nathan and Emily’s emails, they would have discovered that just six months earlier they had visited the West Bank, and that they were members of an organization called the ISM, or International Solidarity Movement, which according to its website, is a “Palestinian-led movement committed to resisting the longentrenched and systematic oppression and dispossession of the Palestinian population using nonviolent, directaction methods and principles.” As you can imagine, affiliation with the ISM does not curry much favor at Ben Gurion Airport.

Nathan Filer: They’re certainly not popular with the Israeli authorities, I mean they’re not popular because they’re one of the more effective organizations. I’m not a spokesperson for them, you know, but I go back and sort of stress you know they’re a nonviolent, directaction organization, and that’s a very effective way of making a point.

Mishy Harman (narration): ISM volunteers from all over the world come to the West Bank and Gaza to stand alongside Palestinian farmers, protect olive groves, teach at schools, demonstrate at check points. And in October 2011, Nathan and Emily decided to sign up for one of their missions, in Hebron, where they mainly volunteered at the local Cordoba School. This was their first time in the region, and the experience had a profound impact on them.

Nathan Filer: There is not very often, is there, in your adult life, I suppose, that you like have a day that is nothing like a day you’ve had before. You know, mostly our days are pretty similar or a lot of them is the, you know, same old same old. But certainly going there, you know, I had not been involved in activism work at all. I’d not been to that part of the world at all, you know. And so it was completely new experiences.

Emily Parker: Yeah, it was just the first time we went, it was an amazing…

Nathan Filer: Still feels like the most, certainly one of the most important experiences of my life, well both of us, wasn’t it?

Emily Parker: Yeah, yeah. We just met so many lovely people, and, you know, inspiring people, and… Yeah. It wasn’t about being like excited to be in like the protests and things, was it? You know, we were passionate about the human rights issues and things that that was what we were there for.

Mishy Harman (narration): After three weeks in Hebron, they returned to their lives in Bristol. Emily worked for a community mental health team, and Nathan was just finishing his first novel, The Shock of the Fall, which later won the prestigious Costa Award and was translated into thirty languages. Half a year later, they decided to go back to Hebron, for a second round of volunteering. That’s how they found themselves in that interrogation room where they asked to hand over their email passwords.

Nathan Filer: If the authorities at the airport know that you are with the International Solidarity Movement, they will not let you in. No country has to let people in, so, you know, it doesn’t matter that it’s a perfectly legal organization even under Israeli law, if they know you’re part of that they won’t let you in, and we were a part of that. So we had reason to be, reason to be nervous.

Emily Parker: And then, quite quickly, they separated us.

Nathan Filer: I was, you know, trying to be polite, and small talk, and I asked their names, you know, ‘cuz they’d asked my name (well, they knew my name, they confirmed it, it’s in my passport). And I said, you know “what’s your name?” And the guy sat at the table said his name was Israel. And for a heartbeat I… I think I just believed him, I just… You know, his name was… And I looked to the guy standing beside him and he said his name was Tel Aviv. And I thought, ‘ah! the flow of information is only going one way,’ [Nathan laughs]. Yeah. And you know, I laugh ‘cuz, it does, you know… It amuses me, but again, at the time, yeah this was frustrating. And yeah, I felt angry and upset, and also feeling like, you know, I still don’t know what’s happened to Emily. I don’t know whether she’s gonna get into the country or not. I need to try and make sure that I do, I don’t know what she said, you know, so much going on in my head at this point.

Mishy Harman (narration): Nathan tried to get some answers. He asked what was going on with Emily.

Nathan Filer: And Tel Aviv said, “she will be deported.”

Mishy Harman: What were you told? Were you told that he was being deported?

Emily Parker: Ahhh… I can’t remember if at that stage.

Nathan Filer: I feel like I was more interested in your fate than you were in mine. [Emily and Nathan laugh]. I was like: “What you doing with my girlfriend? What’s happening to her? What going…” [Nathan laughs].

Mishy Harman (narration): But no one was interested in answering Nathan’s queries. They were the ones asking the questions.

Nathan Filer: Before he asked about ISM, Israel leaned across the table, and looked at me and said: “Now, I’m going to ask you a question, but before you answer, I need you to think very very carefully, because I already know the answer.” Then I… Yup, I lied. Lied about all of that. At one point I said, again to trying to sort of fill the space, “what do you think I’m a terrorist?” And at this point like it was like the whole atmosphere in the room changed. And he just stopped and said, “say that again?!” And at that point I was quite frightened I suppose. ‘Cuz I’d just like… I’d said the word, I suddenly thought ‘oh, I’ve said the word “terrorist.”’ I was just being a scaredycat, I suppose, really. But I kind of said it again, and he said, “no, if we thought you were a terrorist, you wouldn’t be here talking to me now.”

Mishy Harman: How long were you interrogated for?

Emily Parker: Hours and hours!

Nathan Filer: Hours. Yeah, I think by now… It’s now a good six hours has probably gone by.

Mishy Harman (narration): At the end of all this, no big surprise here, Nathan and Emily were each individually told that they could not enter the country, and that they would be deported back to the UK.

Nathan Filer: We flunked our interviews, yeah, we flunked our interviews.

Mishy Harman (narration): Their passports were stamped with a big ‘rejection,’ their fingerprints were taken, they were photographed with some special 3D camera, and then, they were driven in an armored vehicle to the detention center, right near the airport, where they’d spend the night till their plane left the next morning. That’s where they first saw each other, after all these hours of interrogation apart.

Emily Parker: And then we were searched pretty much straight away when we got there, weren’t we?

Nathan Filer: Well, there wasn’t many people there, well, it was just a guy, wasn’t it, who was there at that point, and he was quite a young guy, wasn’t he? And he looked…

Emily Parker: Yeah, he was sweet and quite kind of apologetic in a way, like you know, he was just, you know… You could tell he didn’t especially want to be doing his job. He said: “Right, I need to search you again.” This is the first time that we were kind of kept together to be searched.

Mishy Harman (narration): Now, this entire time, Nathan wasn’t only trying to hide something from the airport security folks. He was also keeping a secret from Emily.

Nathan Filer: So all this time I’ve had something in my pocket, which I didn’t want Emily to know about. And he patted me down, and he felt it in my pocket. And sort of said, you know, “what’s this?” And I remember saying, “ah, you’ve ruined everything!” And so then I sort of took it out of my pocket and he opened it, and there was the… the ring

[Emily and Nathan giggle].

Emily Parker: So I saw it then! And I think I sort of melodramatic burst into tears.

Nathan Filer: Yeah, so you came over and we had a hug and this, this guard was ummm… I mean he couldn’t have been sort of more apologetic, really, at this point, ‘cuz he’d a, yeah…

Emily Parker: Yeah, he was really well, awkward, I guess [Nathan laughs], and you know, it was like potentially quite an intimate moment [Nathan and Emily laugh] yeah and then…

Nathan Filer: He said “let me get you a drink.” And you said “champaigne?” [Nathan laughs] And he said: “I’ll get you a Sprite.” [Mishy laughs] And bless him he did, yeah, he went off to the vending machine and bought us a can of Sprite, yup.

Mishy Harman: And when were you planning on giving this to Emily?

Nathan Filer: Well, I hadn’t decided that I definitely was. [Nathan laughs]. I’d had a conversation with my mother before I went out, so it wasn’t the final ring that’s on Emily’s finger. It was one that I borrowed from my mom so just before going to the airport and I was like, ‘well I might, you know, maybe like we’ll be in Ramallah or something and there will be a beautiful sunset and just, you know, I just want to keep the options open.’

Mishy Harman: So basically this detention guy kind of pushed you into proposing?

Nathan Filer: Yeah! [Nathan laughs].

Emily Parker: It sounds quite a lot less romantic, like a forced marriage.

Nathan Filer: Well, you know, I had the ring, so there was clearly… There was some intent there, but yeah, it wasn’t going to happen at this time.

Mishy Harman (narration): Anyway, back in the detention center.

Nathan Filer: We were taken outside, into like an exercise yard, I suppose, with high fences. And we were sitting on these concrete steps and it was night now, and a pitch black sky, and there was, I remember, a security light at the end of the exercise yard. A bright, white security light shining down on us that sort of looked like a full moon. And the guard at this point, he… sort of, he couldn’t kind of leave us completely alone, but he was clearly trying to give us a bit of privacy, and he sort of took himself away to the far end, or busied himself with some work, ah… to give us a bit of space. And there was a moment of calm and quiet, and we sat there together on the step. And Emily realized that…

Emily Parker: Yeah, you hadn’t actually asked me…

Nathan Filer: Yeah. Yeah.

Emily Parker: If I’d marry you. And we’d just kind of jumped ahead and… Well, I had jumped ahead and started crying. [Nathan and Emily laugh].

Nathan Filer: Yeah, so it was ahh… Yeah, it was time to actually pop the… pop the question. And ummm… I remembered something that had been said to me earlier that day, so I looked at Emily and said: “I’m going to ask you a question, but before you say anything, I want you to think very very carefully, because I already know the answer.”

Emily Parker: Cocky! [Nathan laughs].

Nathan Filer: Well, we’d already done the crying, so it was a fair risk to take, yeah. [Nathan and Mishy laugh].

Mishy Harman: So what did you say?

Emily Parker: I said yes! [Nathan and Emily laugh].

Mishy Harman (narration): We have spent the last six months trying to track down this guard. We’ve pulled every possible string with the army, the police, border control, airport security, even the Shabak. We got nowhere. But if you happen to be listening to this, dear Mr. guard, please get in touch. Emily and Nathan would love to invite you to Bristol for a Sprite, and they have something to tell you.

Nathan Filer: The engagement isn’t the end of, you know, it isn’t the end of the story. It might be a nice… like feel like the end of a story in terms of it’s a neat little narrative arc, but it wasn’t the end of our time there. And we were like, for that sort of moment of happiness, we weren’t in a… we weren’t in a terrific place.

Emily Parker: After we’d been in the courtyard, and he said, you know, that we now have to go to the cells, and we asked whether we could go together, and he said that normally we wouldn’t be able to, but because we were now engaged that he’d put us in what he called a family cell, which was a depressing thought. So that was… It was lovely of him.

Mishy Harman (narration): Still, this was obviously not particularly pleasant.

Nathan Filer: You know, being locked up was horrible, horrible experience. And the cell was… I mean it felt so sad as well, because there was a cot in it for…

Emily Parker: It literally was a family cell, you know.

Nathan Filer: Yeah, so there was a cot and you would just kind of imagine a family being locked up and a baby there. [Emily says something inaudible]. Yeah, well yeah, so there was sort of of Disney stickers but all sort of peeled off, and then there was like the most, you know, pretty vile kind of antisemitic graffiti everywhere. Yeah, it was not, you know, the “family suite,” you know. We shouldn’t get carried away. But what it did, what it meant was that we were together for the night, rather than apart for the night. And there is an extra bit to this story as well, of course, that the guard doesn’t know.

Emily Parker: Right, we imagine that maybe he tells people about, you know, this English couple that got engaged on his watch.

Nathan Filer: But he doesn’t know how the story ended. Actually, he doesn’t know the…

Emily Parker: The best bit.

Nathan Filer: The best bit. The best bit. So we were locked up, and we were locked up overnight together and we were newly engaged, and yeah… All a very conflicted situation, but in any case, nine months later, almost to the day, our daughter was born, our little girl was born. And we named her Iyda, which is an Arabic name and it means to return.

Mishy Harman (narration): Nathan first told this story in an essay called “Rules of Engagement,” for the New York Times Magazine. We recorded him and Emily in their living room, in Bristol. It was literally the middle of the night, and we were all trying to keep it down, so as not to wake up Bill, Iyda’s little brother, who was born this past summer. Happily for him, I guess, he was not conceived in the cell of a detention center. Now, if Nathan and Emily’s story takes place in a post 9/11 world of heightened security and sniffer dogs, our next story comes from an entirely different era.

Julie Subrin takes us back to the sixties, and to one fourteen year old boy, who just had to fly.

Act TranscriptReporter: Did you know, when you did it, what you were doing?

Victor Rodack: I knew what I was doing, I knew I’d get into trouble, but still I thought maybe it’s worth it.

Reporter: How much do you really regret it?

Victor Rodack: Well, I regret the worry I had to cause to my parents. That’s all. I’m sorry I did it. But I think if I had the same opportunity I’d do it again.

Reporter: Have you done anything like this before?

Victor Rodack: No, never!

Julie Subrin: If you’re a certain kind of kid a dreamer, say, maybe something of a loner foreign places can take on mythic qualities in your imagination. They represent everything your boring old life isn’t. For some kids it’s space, or the moon. For me I grew up in the 70s it was the Soviet Union, where in my mind, little girls got to wear poofy red bows in their hair, and drink hot chocolate all the time since it was so cold outside. For Victor Rodack? That place was Israel. Victor grew up in Far Rockaway, a scrappy seashore community in Queens, New York. He says the Israel infatuation didn’t come from his parents, who only seemed to remember they were Jewish when the high holidays rolled around. Instead, it started with a library book…

Victor Rodack: called, uh, Journey to the Promised Land. It was about a Yemenite family and their trip to Israel. And I discovered Israel. And what impressed me was, Israel seemed to be a place where children (I was a child, obviously, at the time) were welcome. You know, stories about the Holocaust and children who were orphans were brought to Israel and taken care of and given love and attention, and all these wonderful things…

Julie Subrin: As the oldest of 4 kids, maybe Victor felt like those wonderful things were in short supply at home. Anyway, at about that same time, Victor also fell in love with international travel. Or at least the idea of it. This, he’s sure, came from his mom.

Victor Rodack: My mother, when we were kids [laughs], she would take us down to see big ocean liners the day that they sailed, because back then you could visit these big ships… She had the wanderlust, she wanted to travel, she never traveled very much but she wanted to go to Europe, and if we misbehaved, she’d threaten us, and say, “You know, if you don’t behave, I’m not taking you on the boat to Europe.”

Julie Subrin: Around the time of his Bar Mitzvah, these two passions – Israel and international travel – were starting to converge into some sort of a plan. Victor had studied Israel’s history, it’s monuments and geography and topography. And he was determined in that way that only a fourteen year old boy can be determined to get there. One morning, he noticed an ad in the weekend newspaper, next to the listings for summer camps and language programs.

Victor Rodack: Come and spend an academic year in Israel. It was for 10 graders.

Julie Subrin: Victor desperately wanted to apply. But there was just one problem.

Victor Rodack: You know my background was very modest. There were 4 kids in the family. My father was sort of like blue collar, worked on the waterfront. We lived in public housing and we had very limited means. But nevertheless, when I saw that particular program, high school year in Israel, I wrote to that school, I wrote a letter, and basically said, “look, this is who I am, this is what I want. I don’t think it’s fair that just rich kids get to go to Israel…” You know, I was a kid… and lo and behold, a week later, I come home from school and my mother’s got this strange expression on her face, and she tells me she got call from a rabbi, affiliated with this program, and they want to figure out a way for me to go. So I was beside myself with excitement. But this was, I should tell you, I guess late May, 1967, and few days later the war started, the June war. And somehow we lost contact, there was no followup, I never heard from them again. And that was the end of that. So now, I had to go to Plan B, I had to figure out some other way to get there.

Julie Subrin: Victor lived pretty close to JFK International Airport, and he’d already established himself as kind of an airplane nerd…

Victor Rodack: Uh, in junior high school I sat in the back of the room, and I could see the planes coming in, and I would tell people “oh that’s Alitalia,” or “that’s Aerlingus,” and when it was an El Al jet, I was like very excited.

Julie Subrin: Now, he started riding his bike out to JFK and snooping around whenever he got the chance.

Victor Rodack: I would go to the airport, and I was observing, how flights were boarded, documentation you needed to get on the plane. And then, as a test case, I tried to get on a plane, that was British Airways. At the time it was BOAC British Overseas Air Corporation. I just wanted to see how far I could get. So I get down to the tarmac, and I go up the steps, no one stops me, and I’m just about to get on the plane when a gentleman in a uniform sees me, and asks me what am I doing there, and I think I said something very naïve, like “oh, I just wanted to look.”

Julie Subrin: The man in the uniform was not amused. He marched Victor into his office, and did his best to scare him straight.

Victor Rodack: Not quite threatening, but telling me I can get into serious trouble, and he would tell my father.

Julie Subrin: Victor was undettered…

Victor Rodack: For me what I took away from it was, I can get on an airplane!

Julie Subrin: Victor knew there was just one direct flight a week from New York to Tel Aviv. That flight left every Sunday evening at 7pm.

Victor Rodack: So the day came, in August. I think I had an argument with my father, just the pretext that I needed to make this decision to go. So I called up my friend Dennis, and it was you know with some forethought, I didn’t want to just disappear. I felt responsible for my parents, I knew that if I didn’t come home, they would freak, it would be horrible. Plus I had three younger siblings, you know, they needed to have parents. You know, so I was just thinking of all these things. So anyway, I speak to Dennis, he says OK, he comes with me to the airport, it wasn’t the first time, and we go to the El Al terminal. And, you know, it’s that excitement of a departing flight. People are there checking in, luggage everywhere, family everywhere, Hasidim, you know the whole thing. And it dawns on me that you need a boarding pass to get on a plane. This was my revelation. Now, it came as a shock because here I am all set to go and now, what am I going to do. Low and behold, I see at the check in desk a pile of these boarding passes, and so I guess maybe the most high risk moment of this whole thing was walking over to the edge of that desk, that check in counter, and blatantly just reaching over and taking one. And I really expected someone would see me… but nothing happened! So now I had a boarding pass… I was all set to go. [laughs] And so now they announce overhead, you know “departure, gate 24.” So I knew from my research everyone was going to go down gate 24, they might have to show tickets, passports, whatever, but they’d end up with their boarding pass. But if I went down to gate 23, (remember this was in the 60s), there was nobody there, there was no checkin, there was nothing. So everyone’s going down gate 24, I go down gate 23, Dennis is with me, we go out the door onto the tarmac. And at that point Dennis says to me: “this is crazy, you can’t do this, I’m leaving!” And so Dennis turns around and just walks away from me. So now, what are my options? Am I going to follow Dennis, like a… you know… with my a tail between my legs?

Julie Subrin: Victor stayed put.

Victor Rodack: So now I see people getting on the plane, and they had their boarding pass in their hand. But part of the pass was removed… so I took off the top of mine, put it in my pocket, and went like everyone else… first decision, people going up front of plane and back of plane. Boeing 720B to be precise. Anyway, so I decided to walk towards front of plane. Go up steps with everyone else. And now I’m thinking, what am I going to do if that seat is taken. Can’t just say “whoops, I’m on the wrong plane, gotta go!” I knew it would be serious trouble. But I go, find seat, no one in it. Sit down, by the window on the left side. And there’s a seat between me and the aisle seat, woman sitting in aisle, very nice, she asks me “oh have you ever flown before?” She asks me. I say “No, I’ve never flown before.” She’s making pleasant conversation. Then I feel hand on my shoulder and I look up, and it’s the flight attendant offering a little basket of candy, so I took some candy. And so I’m sitting there, and now I see a man in a uniform walking down the aisle counting – counting people – so I’m thinking oh wow, the jig is up. He goes by, nothing happens. And now, it gets very very quiet. See, they had closed the door. And now they say overhead something in Hebrew, and suddenly this thing is slowly starting to move. And they say “welcome aboard” they say it in Hebrew and then they say it in English we’re flying to Tel Aviv blah blah blah, and I’m like in some altered space. You can’t imagine how excited I was. But so now we’re moving past the terminal, and everyone’s waving at the plane, and that’s where I would be in the past, watching the plane leave. And now I’m in the plane. And we’re proceeding through the taxiways, and then there’s another announcement overhead. Now at this point I’m very anxious, because until the plane gets off the ground, I’m at high risk. Plus Dennis, my loose canon buddy, he’s out there somewhere, I don’t know what he’s doing, what he’s saying, who he’s talking to. So I’m sweating. And so there’s this announcement in Hebrew, there are 12 planes ahead of us… will be delayed 25 minutes. So that’s another 25 minutes of suspense. But those 25 minutes come and go. And the next thing I know this plane swings around … and we’re on the runway and it starts to accelerate and get very loud. And get very fast and we’re going and going and suddenly we’re up in the air and I’m looking out the window and then the plane actually banks to the left so we’re right over Jamaica Bay. Now remember, I’m from Far Rockaway and I know this geography very well. So now we’re flying over the subway line that I just got off to get to the airport. And then we’re flying over Rockaway and I see the projects where I live, I see Junior High 198 where I just graduated a moment later I see Far Rockaway High School that I’m supposed to start in the fall. And it’s like, “Goodbye!” I was on my way. And there are little puffy clouds, and I’m flying over the south shore of Long Island, and it’s just amazing.

Julie Subrin: Soon the sun set, and it was dark out the window. The stewardesses came around with dinner trays.

Victor Rodack: And I’m just polishing off my dinner, when I hear a flight attendant behind me you know coming down the aisle, calling someone. And it was, to me, obviously, my name. So I ask her are you looking for me? What’s your name? “Oh, this is my name, Victor Rodack.” “May I see your ticket?” And I say, “well I don’t have a ticket, but I have a boarding pass, would you like to see that? And she says come with me. And I get up and I go with her down the aisle to the cockpit of the plane. Now I’m in the cockpit of the plane. And it’s dark and all the little lights are glowing, you know those little dials and everything. And the pilot is sitting right there and he starts talking to me. And I guess maybe the second bravest thing I did was say to him I’m not going to answer any of your questions unless you promise me my father isn’t going to have to pay for this. I can’t believe I said that! But I did. And he actually promised. And so I tell him the story. He wants to know, you know, what the deal is. And I explain whatever I had to explain, and that was that. So I’m told to go back to my seat, and as soon as I get out of the cockpit, I’m surrounded by crew members, and they’re all excited. And you know they’re saying to me, well if you stay in Israel you can stay with me, I have a son your age, you can stay with us in Herzliya, I remember that specifically. They were very very nice. So now I’m going back to my seat, you know we spend the night on the plane now it’s the morning, time goes by, I remember looking down and seeing France with my own eyes… the Massif Central, which is the central mountains of central France. Recognize it, flying over Europe, then Greece. Then the crew invites me up to the front of the aircraft, they have a little compartment where they stay I guess, and I’m thinking ‘oh, isn’t this nice, they want me to be with them, you know.’ so I go up there, sitting at front of plane, and now, the moment I’ve been waiting for, we’re descending descending descending, and now I see the coastline of Israel.

Julie Subrin: Looking out the window, Victor began to recognize all the landmarks he’d seen in books and magazines – the Hilton Hotel in Tel Aviv, the Mann Auditorium. But this time it wasn’t a photograph. It was moving. Little cars were crawling along the roads. People were living their lives. Going to work. Victor was stunned. He had actually pulled it off. He was seeing Israel with his own eyes.

Victor Rodack: And so the plane gets lower and lower and lower and lands. You know, the engines are reversed, it gets very loud, and then we’re slowing down and … I remember being struck by this teeny weeny little air terminal, coming from JFK, there was this little airport. And then the plane stops, and two police cars are driving out to the plane. And I’m the first one off the plane, and I’m escorted by the crew, and I’m put in the back of a police car, and they take me to some place, and I guess I was interrogated. You know, they wanted… All kinds of questions, there were all kinds of people there, some in uniform, some not, I remember there was a pregnant woman there, they were all asking me questions. It was just an interview… And then they sort of ended up by saying, “well this plane is refueling now, it’s turning around, and it’s going back to New York in an hour, and you’re going to be on it.” And at that point, I sort of had a fit. I said “no,” I didn’t want to go back, “please don’t make me go back.” You see, I’ll tell you what my plan was. My plan was to sneak off the plane the same way I snuck on the plane, and find a bicycle, and find a kibbutz, you know go off on a bicycle and find a kibbutz, out and then pretend I didn’t know who I was, and then they’d have to adopt me. That was the plan. That I had. It was not going to work, obviously, they had me. But I wanted to stay! I mean, I came all this way…

Julie Subrin: And so it went on – more questions, more heated debates behind closed doors. Then, finally, the airport security folks presented him with their decision:

Victor Rodack: “OK, we’re going to let you stay, for one day. But you have to sign this paper that says you’re not going to run away.”

Julie Subrin: Victor signed. And the clock started ticking.

Victor Rodack: And so then, I was taken to the home of… I believe he was either the head of the airline, El Al, or the head of the airport.

Julie Subrin: Yup, that’s right. After running away from home, sneaking onto an airplane, and traveling roughly 5600 miles across the world for free, Victor was given the royal treatment. They tried to pack as much of Israel into a single day as they possibly could. Back at the home of the head of El Al or the airport or whoever that guy was, neighbors crowded around Victor like he was some kind of celebrity. After that, he and the official’s family went out for a nice bike ride, followed by a tour of Jaffa, and Ramle. And then he was bundled into another family’s car and whisked away… to Jerusalem.

Victor Rodack: We get to Jerusalem, and they bring me to what I’ve since learned now was the Damascus Gate, and we walked through the Damascus Gate, and suddenly I was in the old city of Jerusalem, and we went all the way to the Wall, the Kotel, and I put on tefillin, and I said the bracha, whatever they told me to do, it was a state of disbelief, just a state of disbelief.

Julie Subrin: From there, he was shepherded back to Tel Aviv, where he stayed the night.

Victor Rodack: And the following morning I went with the older son to get bread and it was just fun to be in this environment of leaving the house, walking down a street, going to a bakery, just like normal life? But in Israel.

Julie Subrin: Victor spent his last few hours touring Tel Aviv with his hosts. The wife took him to the top of the tallest building in town, Migdal Shalom, to get a full view.

Victor Rodack: And then, she took me to the airport, where I was catching the flight back to New York.

Julie Subrin: The return flight was less exciting than the stowaway leg the day before. They made a stop in London, but…

Victor Rodack: I was not allowed off the plane – I had no documents, I had no passport, I had nothing…

Julie Subrin: Then, just over 48 hours after he’d left, Victor was back where he started, at JFK Airport. He stepped off the plane, preparing himself for his parents’ wrath, and whatever other fallout was coming his way.

Victor Rodack: It was dark by then. And we were met by an El Al I guess PR person – a tall, beautiful woman who led me into a room… where there were reporters! and I actually had a news conference!

Julie Subrin: Victor still has a recording of that interview, on a vinyl record.

Reporter: Hello Vic.

Victor Rodack: Hello.

Reporter: How do feel?

Victor Rodack: Fine and tired.

Reporter: What did you do?

Victor Rodack: Just, took a plane to Israel.

Victor Rodack: [laughs] My parents were there and these reporters were there and some other folks, neighbors of ours, and they interviewed me.

Reporter: When you say you just wanted to go, was it that you wanted to get away for a while?

Victor Rodack: Possibly, I’m not sure myself, I just felt like leaving. That’s why I left.

Reporter: So how do you feel now that you’ve been over there, did you like it?

Victor Rodack: I enjoyed it. I had a wonderful time in Israel.

Reporter: Would you go back?

Victor Rodack: Yes, I would – and I will.

Reporter: The same way?

Victor Rodack: No, I’ll be a paying passenger.

Julie Subrin: At the end of this impromptu press conference, the reporters turned to Victor’s father.

Reporter: Mr. Rodack, it’s traditionally dad’s job to administer discipline. Have you given any consideration as to what you’re going to do?

Mr. Rodack: Well I think when we get home, we’re going to have a long talk, and my wife and I will decide on what we will do in regard to Victor.

Reporter: Are you a whipping father, or do you rely on psychology?

Mr. Rodack: No, I can understand some of the things that motivated him, but I certainly do not condone what he did. And we’re going to take that up when we do get home.

Reporter: Does El Al feel that you have to pay?

Mr. Rodack: I have no idea at this time.

Reporter: What if you do?

Mr. Rodack: Well, he’s gonna have empty pockets for a long time.

Victor Rodack: And then, I went home. My parents… You know, I got a ride home with neighbors, we drove back to the house, and bingo, I was back.

Julie Subrin: Of course, there were consequences. Victor’s parents were very upset with him.

Victor Rodack: They sent me to see a shrink, which I guess, you know, was to their credit, it was probably not a bad idea, but I was mortified at the time.

Victor Rodack: So these are my souvenirs…

Julie Subrin: Victor shows us a collection of yellowed postcards and newspaper clippings.

Victor Rodack: [read headlines] ‘Boy’s Ad Lib Trip to Israel’ – Long Island Press. I have an article here from L’information, which is a French Israeli newspaper. This is from The New York Times, this little bit. ‘My Son the Globe Trotter,’ from the New York Post. That’s me with my mother…

Julie Subrin: There he is in a faded photo, a perfect specimen of early adolescence, taller than his mom, but shorter than his dad, skinny, and with a sheepish, boyish grin – and just a hint of pride. Those 48 hours made Victor kind of famous around the neighborhood, and at Far Rockaway High School. To this day, on the school’s listserv, people post things like: “I would love to find out what ever happened to Victor Rodack, class of ’70. He achieved notoriety when he stowed away on an El Al flight to Israel. Rumor has it he may be in Jackson Hts. Anyone know anything regarding his whereabouts?” When he was asked about it at the time, in August 1967, Victor was pretty sure about his future.

Reporter: Do you think you’d like to go back there, to live, or to study?

Victor Rodack: Yes, definitely.

Reporter: So you said you’re going back. I just wonder what makes you so definite.

Victor Rodack: I just am, I know I will. It’s inevitable.

Julie Subrin: Given all that, you might expect that Victor headed off to join the IDF or a kibbutz, just as soon as he was old enough. But over time, Israel that faraway place that welcomes lonely children from everywhere was replaced in his mind with a more complicated reality – one he visits, and loves, but not somewhere he sees himself living. Still, he’s got those souvenirs, and newspaper clippings, and that vinyl record, to remind him that when he was just 14, he made the trip of a lifetime.