Let’s face it – when it comes to Israel, everything is complicated. Politics are complicated, religion is complicated, democracy is complicated, the conflict is complicated. Even our complications are complicated. These are the things that take us out to the street. That make us shout, and cry. That fill us with hope, and – just as often – plunge us into utter despair. But there is (seemingly) one island within Israeli society that escapes complexity, and brings us together more than it divides us: Israeli music. Or so, at least, we thought.

In this special mini-series, we set out to explore Israeli society – warts, rifts and fuzzy togetherness alike – through the stories of some of the country’s most iconic tunes.

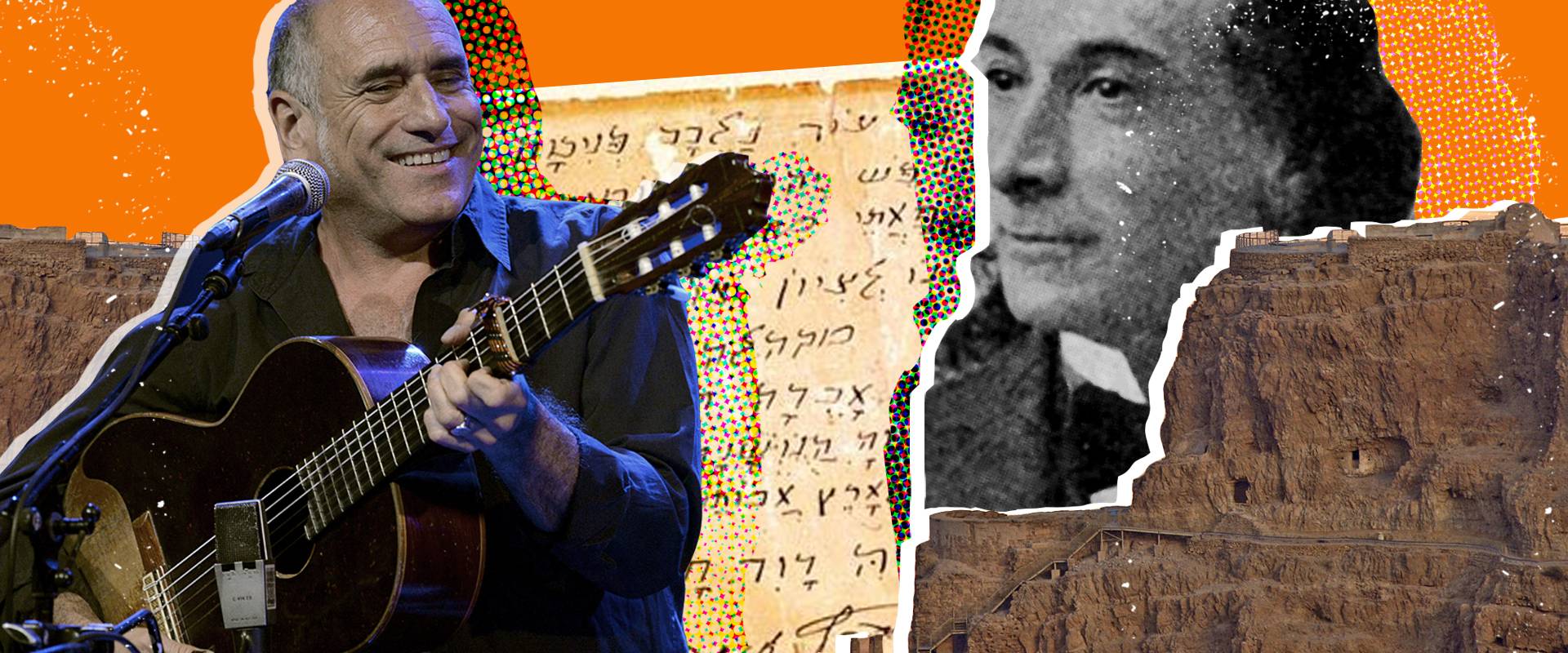

Mishy Harman talks to Mitch Cohen, the International Director of Ramah Camps and to author David Grossman, the winner of the 2017 Man Booker International Prize, to understand what is so unifying about Israeli music. He then checks out their theories with David Broza who discusses his 1991 hit song Mitachat La’Shamayim (‘Under the Sky’).

Act TranscriptDavid Broza: Yihiye Tov is always… over forty years of singing it, maybe eight thousand times I sang it, and I gotta say, I’ve never had to duplicate it. It’s rewritten every day. Again and again and again. I always say it’s almost like doing the amidah, when you pray three times a day. You know, the real believer, will do the amidah, the shmona-esre, everytime as if it’s the first time he’s ever done it because he’s actually putting himself back on course. So I don’t pray, I sing Yihiye Tov. That is my prayer. I contemplate, I mean every word. I don’t care or who I’m singing for – the hillbillies, for rednecks, for white trash, for Spanish, for gypsies, for whatever – it’s always Yihiye Tov in the end, and they get it. They don’t understand a word, and they get it. It’s odd because it’s also the first song I ever wrote. I wrote it right here, on this sofa. Forty years ago.

Mishy Harman (narration): Let’s face it, when it comes to Israel, everything is complicated. Politics are complicated. Religion is complicated. Democracy is complicated. The conflict is complicated. Even our complications are complicated. These are the things that take us out to the street. That make us shout. And cry. That fill us with hope, and – just as often – plunge us into utter despair. But Israel’s now seventy. And well, my mom always told me that there’s a time and a place for everything. And a seventieth birthday party? It’s most definitely not the time or the place for shouting and yelling. So over the past few months, we set off in search of a unicorn. An island within Israeli society that somehow escapes complexity. Sports wasn’t it. Neither was food, or history. We circled through ethnic groups, religious traditions, high-tech innovations, people who were all born on Independence Day 1948, and even folks called Israel Israeli. But somehow all those directions led us straight to arguments, and battles, and wars. Till, one day we found it. The much-coveted unicorn. The island of Israeliness that brings us together more than it divides us.

What is it about Israeli music that unites us, that allows people from different political persuasions, from different social spheres, from different backgrounds and ethnicities and religions even, to come together and sing? Here’s Israeli author David Grossman.

David Grossman: There is this Israeli phenomenon of shira be’tzibur.

Mishy Harman (narration): Singalongs.

David Grossman: Singalong? Yeah. That people are gathering, usually at a home, and maybe they screen the words of lyric, and there is someone with a piano or accordion and we are all singing. And by singing, I feel (and I love to sing in these gatherings!) as if we touch the basis of our existence.

Mishy Harman (narration): I also love these singalongs. When I was a kid our neighbors, the Tokatlis, used to host them. And I remember how I’d climb over the fence and see the husband, Pinhas, who was later killed by a suicide bomber, play his accordion. These were songs of a different era, of pioneers, of Palmachniks, of Eretz Israel ha’yeshana ve’ha’tovah, ‘Good Ol’ Israel.’ These songs, till today, make me – and most Israelis I think – feel at home. But Israeli music doesn’t just unite Israelis. With all due respect to ICQ or cherry tomatoes, it’s one of our greatest exports – simple, beautiful, accessible.

Mitch Cohen: It just brings a smile to everyone’s face and makes everyone feel great about Israel. And for a moment, at least, we could stop talking about all the complexities of Israel – conflict, challenges – and just really learn to love that sense of culture and therefore love the people and the Land of Israel.

Mishy Harman (narration): And you probably know exactly what Mitch Cohen, the International Director of Ramah Camps, is talking about. I mean, just think of it: I bet many of you have found yourselves, whether it was at summer camp or in a youth movement activity, sitting around humming some songs like, well, like these ones…

[Arik Einstein medley]

Mishy Harman (narration): But it isn’t only Arik Einstein that makes us feel all tingly inside and connected to Israel. There are other artists who have written songs that made it into the pantheon of Israeli music ‘classics.’ One of them, a song that I grew up singing, actually started its life in English, far away from all the hustle and bustle of Israel.

David Broza: The original name of it is ‘The End of the Beginning.’ Cuz’ I wrote it in English originally.

Mishy Harman: Really?

David Broza: Yeah, yeah.

Mishy Harman (narration): That’s David Broza, who we heard talking about Yihiye Tov at the very beginning of the episode.

David Broza: I wrote it in a little town, on the most northeastern tip of the United States. Right under the border of Canada, in a place called Eastport, Maine.

Mishy Harman (narration): The year was 1990.

David Broza: Just before the Gulf War.

Mishy Harman (narration): And David, one of Israel’s most celebrated musicians, was in a funk. He had come to Eastport in search of a local poet, only to discover she had recently left town.

David Broza: There was a big sky, and it was already like, twenty degrees fahrenheit, so it’s really cold.

Mishy Harman (narration): He sat down, took out his guitar, started playing some bluesy chords and singing to himself.

David Broza: “This is the end,” I was really down. “The end of the beginning, and I’m changing, with the winds of time.” I was like, felt like, ‘OK, this is the end.’

Mishy Harman (narration): A few months later, the Gulf War began. Israel was bombarded by dozens of Iraqi scud missiles and people constantly had to rush to the nearby miklat, the shelter, in the middle of the night.

David? He was living in New Jersey at the time, far away from all the balagan. But one of his good friends, a guy called Meir Ariel, was back in Tel Aviv, where most of the scuds were falling. Meir was also a very famous Israeli singer-songwriter. (Remember his name, we’re going to meet him again next episode). Anyway, all the stress and tension of war, it was too much for Meir.

David Broza: He couldn’t stand the scud, and the threats, and the gas masks.

Mishy Harman (narration): So Meir and his wife Tirtza packed up their kids, and took refuge with David, in the Garden State.

David Broza: So he came over, and his son Shachar heard me play this song to myself, and he said, “what is that?” And I said, “nothing.” He said, “oh my dad should look at it.” So Meir took it, and went to a quiet corner, it was actually the only corner was in the bathroom, sat there for twenty minutes, and came out with Mitachat La’shamayim.

Mishy Harman (narration): When David released a clip of the song from a sunrise performance in Masada, it became an instant hit.

David Broza: It just went crazy. And it became an iconic song in my career. Before you had, you know, social media, it had a viral effect. And it just, everybody went crazy.

Mishy Harman: Did this surprise you?

David Broza: Everything surprises me.

Mishy Harman (narration): It didn’t take long before Israelis brought Mitachat La’shamayim – ‘Under the Sky’ – all over the world.

David Broza: I can hear my songs being sung in Melbourne, Australia, or in Curitiba, Brazil, or in Brussels, and far away villages and wherever places that people are, you now, in India, Philippines, you know, amazing. It’s beautiful.

Mishy Harman (narration): With its universal message of love and togetherness, Mitachat La’shamayim quickly became a modern-day Israeli anthem.

David Broza: It’s not about Zionism, it’s not about politics, it’s not about, you know, you gotta sing in Hebrew cuz’ you gotta be part of the Israel Story, it’s just a cool song. I don’t preach it. I don’t like to preach, and I don’t like to tell people how things should be. I will do it, and if you watch me, you will know how to do it. And then you can follow. If you like it. And if you don’t, do it your own way.

Mishy Harman (narration): So today, in honor of Israel’s seventieth birthday, we wanted to bring you a few tension-free episodes, during which you can all just sit down in your chairs, relax and revel in the cozy warmth that is Israeli music.

There is one song that has accompanied Israel from the very start. It is sung by children at school ceremonies, politicians at state affairs, athletes at sporting events and soldiers at military marches. But that song doesn’t mention G-d, the Bible or any triumph of modern Israeli history. Zev Levi takes us on a journey through the origins of Hatikvah, Israel’s national anthem, and examines who it represents, and – importantly – who it leaves out.

Act TranscriptZev Levi (narration): In May 2014, Hamas released a Youtube video. It was a song. A surprising song. The Israeli national anthem: Ha’tikvah. Why would Israel’s sworn enemy, an organization that calls for the destruction of the Zionist entity, spend money producing their version of Israel’s ceremonial tune?

Edwin Seroussi: Like you burn the flag in your demonstration, you can burn the anthem too.

Zev Levi (narration): That’s musicologist Edwin Seroussi, who has spent a lot of time researching Ha’tikvah and its significance.

Edwin Seroussi: So singing the anthem is saying ‘I belong to this nation,’ symbolically. A few bars of music and text, and you have the state. You don’t need more than that.

Zev Levi (narration): Today, Ha’tikvah and Israel are basically synonymous. They go hand in hand like pita and hummus. But it wasn’t always like that. There was, to begin with, one pretty important man who did everything he could to bury the tune.

Edwin Seroussi: Herzl, the founder of the Zionist Movement, didn’t like this song very much. Particularly, he really despised the poet.

Zev Levi (narration): Theodor Herzl hated Ha’tikvah because he thought the lyricist was an embarrassment to Zionism. His name was Naftali Herz Imber.

Edwin Seroussi: He was a very colourful personality; the archetype of the poet. Never had a job. Never could maintain a job, drunk all the time. Living at the expense of others.

Zev Levi (narration): Imber was born in Galicia (modern day Ukraine) in 1856. At twenty-five, he set out for Palestine. And in his pocket, he carried a notebook full of his half-finished Hebrew poems. One of them was called Tikvateinu – ‘our hope.’

Edwin Seroussi: Naftali Herz Imber used to recite Tikvateinu in front of all the farmers here in Palestine.

Zev Levi (narration): As you can imagine, the backbreaking work of land-clearing and city-building didn’t put a poet’s skills in high demand. Doctors, farmers, engineers – sure. Eccentric poets who wanted to discuss mysticism – not so much.

So Imber bounced between communities in Haifa, Yesod Hama’ala, Rosh Pina, Mishmar Ha’Yarden and Petah Tikva. At night, he would perform his poetry for the locals, and during the day, while they worked the fields, he would raid their wine cellars.

In 1886, Tikvateinu was included in Imber’s first book of Hebrew poetry, Barkai – or ‘morning star.’ Now, Tikvateinu is not Ha’tikvah. It’s nine stanzas long and has no music.

But it was popular. One of its early fans was Samuel Cohen, a winemaker from Romania, who started humming a few of the verses to a Romanian folk song, “Carul cu Boi” or “Cart with Oxen.”

The song has no connection to Imber’s Tikvateinu. He just felt that they fit well together.

Edwin Seroussi: And he sings that for his friends. And somehow people like it. And, from the point of view of communications and technology in Ottoman Palestine, it still surprise me how fast this song becomes disseminated.

Zev Levi (narration): The folk tune – now shortened and recognizable as Ha’tikvah – became a grassroots hit. It captured Zionist imagination, and rang true to Jews around the world.

But it only really ‘broke out’ in August 1903, in Basel, Switzerland. The sixth Zionist Congress was abuzz. Representatives were at each other’s throats over the Uganda Proposal – the idea of creating a temporary Jewish state in East Africa.

On one side – those who felt that settling anywhere outside the Land of Israel, even temporarily, was an abandonment of Zionist goals. A betrayal of Jewish history.

On the other – the pragmatists. To them, a Jewish country, anywhere in the world, would save Jewish lives from looming pogroms.

The debate quickly got out of hand, as the representatives felt the weight of a two-thousand-year-long history on their shoulders.

The Russian delegation actually walked out.

But to no avail. The Uganda Proposal passed 295 in favor to 178 against. Those committed to the physical land of Israel had failed to sway the minds of the assembly. So in a last, anguished stand, they rose to sway their hearts.

Edwin Seroussi: They got up and they sing Ha’tikvah.

Zev Levi (narration): This move wasn’t joyful or triumphant. It was a reprimand. They sang Ha’tikvah to remind their peers of one of its lines, ‘ayin letziyon tzofia’ – ‘the eye looks towards Zion.’ And by doing so, a Hebrew poem, penned by a misfit and stuck to a random Romanian tune, became the unlikely political anthem of a country that didn’t yet exist.

Pretty quickly, Ha’tikvah transformed from a Zionist anthem into a global Jewish one. Synagogues printed it in collections of piyutim and read it during services. Publishing houses included it in Passover hagadot, right along with the local national anthem.

In 1945, a BBC reporter witnessed the liberation of the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. He recorded the camp’s survivors performing their first Friday evening shabbat service as free people.

Patrick Gordon Walker: These people knew they were being recorded. They wanted the world to hear their voice. They made a tremendous effort, which quite exhausted them. Listen.

[Ha’tikvah sung by survivors]

Zev Levi (narration): Since Israel’s establishment in 1948, Ha’tikvah has been sung at every state ceremony. Still though, many Israelis claim that it doesn’t represent their Israel. There’s no mention of God, the Bible, or modern Israeli history. In fact, after Israel’s swift military victory in the 1967 war, a Member of Knesset introduced a bill to adopt a new, more triumphant song as the national anthem (you’ll hear all about that later on).

And, of course, Ha’tikvah excludes twenty percent of Israelis.

Rifat Turk: Ha’tikvah is song for Jewish people. Nefesh Yehudi. Nefesh Yehudi. Ani lo nefesh yehudi. I am Arab! Ani nefesh… Arab nefesh.

Zev Levi (narration): Meet Rifat Turk, the Israeli Colin Kaepernick. Rifat was born in Jaffa in 1954, and still lives in his old neighborhood. He’s muscular and bald, with a beaming smile and a powerful stare. In 1976, he became the first Arab on Israel’s national soccer team.

[Sound of Rifat Turk Scoring a Goal]

Rifat Turk: I’m from Jaffa. Go to the Olympic games with the national team? Zeh haya mashehu meyuchad – it’s big big special.

Zev Levi (narration): On the pitch at the start of his first international game, Ha’tikvah rang out through the loudspeakers. But unlike his vocal teammates, Rifat stood silently.

Rifat Turk: I don’t song Ha’tikvah. It’s a… Ha’tikvah – it’s not for me.

Zev Levi (narration): Don’t get him wrong. Rifat was overjoyed to represent his country. It’s just that, while Herzl had an issue with Ha’tikvah’s lyricist, Rifat’s issue was with the lyrics.

Rifat Turk: [In Hebrew] Im ba’himnon haya katuv milim shel ahava, veshel lehitchashev gam bi, ani besimcha hayiti shar et zeh.

Zev Levi (narration): “If the anthem’s lyrics were about love and consideration of people like me,” he says, “I’d happily sing it.”

But some saw his silence as an attack on Israel itself. He told us a few stories of playing for Hapoel Tel Aviv against Jerusalem rivals, Beitar Yerushalaim.

Rifat Turk: “I kill you.” “Go play in the Syria!” “Go Lebanon!” “Go play with Arafat!” It is very very very difficult. But every game! Sometime, I go home, I’m cry, ‘Why?! Why?! What I doing? Just I’m playing football! I’m not kill people. I’m not make a something bad or… just I come to play!’

Zev Levi (narration): Though the Jerusalem club has repeatedly denounced such hooliganism, Abbas Suan knows exactly what Rifat means. He also played for the Israeli national team, from 2004 to 2006.

Abbas Suan: All the Arab players don’t say the Ha’tikvah. Nobody.

[Sound of Abbas Suan Scoring a Goal]

Zev Levi (narration): Right after he scored this game-tying goal in the last minute of a World Cup qualifier against Ireland, Abbas arrived in Jerusalem for a league game.

Abbas Suan: And Beitar Jerusalem bring very big sign.

Zev Levi (narration): The sign read, ‘Abbas Suan does not represent us.’

And that’s really what Ha’tikvah’s struggles have always been about. Representation.

Herzl was a Zionist who thought the song didn’t represent Zionism. Rifat Turk and Abbas Suan are Israelis who think the song doesn’t represent Israel. And they all faced widespread opposition.

In a 1901 letter to Herzl, Imber expressed his delight at the growing popularity of his song. “Although the Zionists treated me ill,” he wrote, “I am still a Zionist and am happy to see my dreams realized.”

So in the end, both Herzl and Imber were vindicated. Herzl was right about Imber, who – in 1909 – died penniless, of chronic alcoholism, in New York. And Imber, the eccentric poet, was indeed immortalized together with his Ha’tikvah. But Seroussi, the anthem expert, told us it might just be Rifat and Abbas who’ll have the final say.

Edwin Seroussi: If you ask me if Hatikva will be the anthem of Israel for ever ever, I cannot tell you a certain answer. It may change.

The original music in this mini-series was composed, arranged and performed by the Mixtape Band, led by Ari Jacob and Dotan Moshanov, together with Ruth Danon, Eden Djamchid and Ronnie Wagner-Schmidt. The final song is a 1950s Tunisian rendition of HaTikvah sung by M. Cohen.

The episode was recorded by Russell Castiglione and Josh Piel at the Dubway Studios in New York, and mixed by Sela Waisblum. It is based on Israel Story’s latest live show tour, “Mixtape.”

Thanks to Rabbi Joy Levitt, Sheila Lambert, Megan Whitman, Amanda Crater, Matt Temkin, Megan England, Sam Brunswick and Philip Sandstrom of the JCC Manhattan, to Robin Mancoll, Art and Annie Sandler, Naty Horev, Melissa Eichelbaum, Gregg Damanti and all the folks at the Virginia Arts Festival and the United Jewish Federation of Tidewater, and to Ben Murane, Lily Shaddick and Leah Breslow of the New Israel Fund Canada, alongside Peter Fehlhaber, Lynn and Aubrey Kauffman, Elisa and Gil Palter, Hanoch Piven, Igor Beregovsky, Naomi Schneider, Ali Ottman, Rachel Misrati, Izi Mann, Guy Arieli and Ilan Ben-Zion.