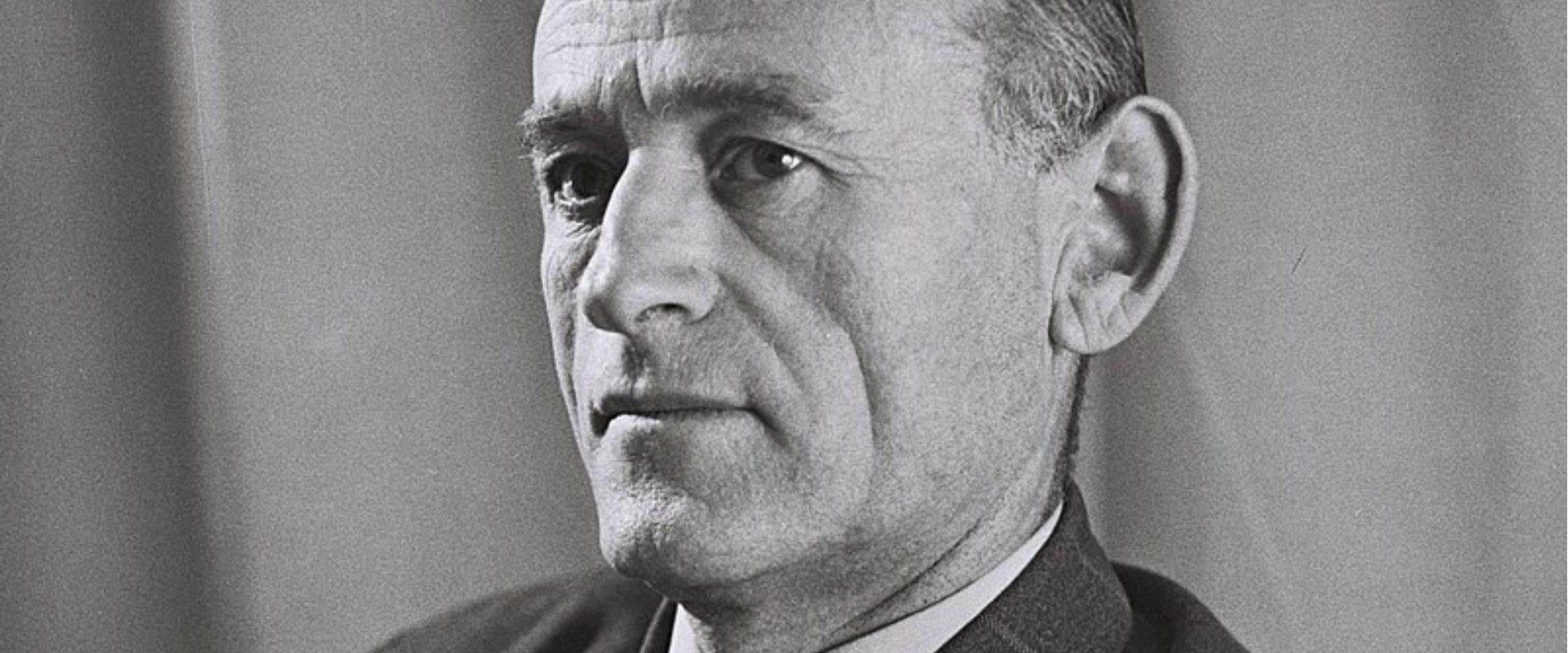

Meir Argov was born as Meir Grabovsky in Rîbnița, Bessarabia, in 1905. At the age of 14, while his family was fleeing civil unrest in the region, his father Yeshayahu – a learned man and a grain salesman – was murdered on the road to Oleksandriia. His remains, in what Argov once called “the land of blood,” were only recovered several months later.

Argov himself attended a cheider, a gymnasium and the University of Kiev. As a prominent young leader in both the Halutz and the Tze’irei Zion youth movements, he was repeatedly arrested by the Russian secret police and was ultimately deported to Mandatory Palestine in December 1924 – a reprieve of sorts, as the much more common option was being exiled to Siberia.

Here in the Land of Israel, he worked in the orange groves of Ness Ziona and Petach Tikvah and later became a fiery labor leader, as the secretary of the Petach Tikvah Council of Workers. He was active in Ben-Gurion’s Labor Party, Mapai, and even served on the Petach Tikvah Municipal Council as their representative.

Though he was already married and a father to twelve-year-old Tamar, in 1941 he volunteered for service in the Palestine Regiment of the British Army. At first, the mostly Jewish enlistees of the 14th infantry company spent their days marching around local parade grounds and guarding warehouses, adhering, he later wrote, to a routine riddled with “suffering, boredom, indifference and despair.”

Only in November 1944, as part of the newly-founded Jewish Brigade, was he finally deployed, reaching Italy and inching towards the actual front. In an essay called “Lit Candles in the Jewish Sector,” he described his first glimpse of German soldiers. They were POWs dressed in rags, being rowed out of the harbor of Taranto. But their sorry state didn’t fool him. Argov wondered whether among them are “those who crushed the skulls of Jews, and showed their valor by slaughtering women and children.” He and his fellow Jewish comrades did nothing, he recalled, but “seal in their hearts a breath of fury.”

Over the course of the next few months the brigade was, at last, thrown into combat. In April 1945 they fought their way across the Senio River – helping win one of the last battles of the war in Italy. The Jewish Brigade, which consisted of some 5,000 soldiers, lost 57 men.

After the war, he helped organize illegal Jewish immigration to Palestine, and – as a member of the National Council – prepared the local postal service for independence. Since neither the name of the state-to-be, nor the name of its currency, had been determined, designing its inaugural stamps could have been a difficult task. But nothing, not even the lack of a name, was going to stop Argov, David Remez and their fellow Zionist leaders. It was soon decided that the first stamps would bear the heading of Do’ar Ivri or Hebrew Post, and wouldn’t depict illustrations of landmarks or landscapes (since – after all – no one knew what the borders of the new State would ultimately be, and which regions would, or wouldn’t, end up being part of the country). Instead, the stamps (which were designed by Otte Wallish – who, incidentally, also designed the scroll of the Declaration of Independence) featured images of ancient Jewish coins from the first and second revolts against the Romans. Issued hastily and under suboptimal conditions, some prints contained spelling mistakes and discolorations. Nevertheless, on the whole, the mission was a success and the stamps were officially released on Sunday, May 16, 1948 – the country’s very first day of business. Today, unsurprisingly, full sets of the original nine Do’ar Ivri stamps sell for hundreds of thousands of Shekels.

Argov – who was both a lifelong Mapai Party member and a traditional Jew who often led services in Ness Ziona on the holidays – called the day of the Declaration of Independence a “Genesis moment.”

He was elected to the first Knesset and appointed Chairman of the powerful Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee – a role he held till his sudden death, of a heart attack, in 1963.

The thirty-seven people who signed Megillat Ha’Atzmaut on May 14, 1948, represented many factions of the Jewish population: there were revisionists and Labor Party apparatchiks; capitalists and communists and socialists; kibbutznikim, moshavnikim and city-folk; charedi rabbis and atheists.

Over the course of the past several months, our team has diligently tracked down the closest living relative of each one of these signatories, and interviewed them. We talked about their ancestors and families, about the promise of the Declaration, the places in which we delivered on that promise, the places in which we exceeded our wildest dreams, and also about the places where we fell short.

And it is through these descendants of the men and women who – with the strike of a pen – gave birth to this country of ours, that we wish to learn something about ourselves.

Today we’ll meet Meir Argov, and his daughter, Tamar Argov de Groot. She’ll present one of the many political perspectives we’ll be featuring throughout the series.

In 1961 Eliezer Whartman of the Israel State Archives conducted a series of interviews with 31 of the 37 signatories of the Declaration of Independence. For the full interview with Meir Argov, see here and here.

For an account of Argov’s life, through a series of biographical sketches and expository essays, see Meir Argov’s 1971 book, Ma’avakim (Hebrew).

For background on the cultivation of oranges in Ottoman and Mandatory Palestine, as well as the public campaigns to include Jewish laborers in the work in the fields and orchards, see Ness Ziona: A City with the Heart of an Agricultural Colony (Hebrew) and this excerpt, from the 1913 film The Life of Jews, about the orange orchards of Petach Tikvah. By the way, the Hebrew word for orange – tapuz – is an acronym of golden apple (tapuach zahav), and was taken from Proverbs 25:11 (“A word fitly spoken is like apples of gold in a setting of silver”). Most scholars agree that the reference in that biblical verse was to ornamental apples made of gold inlaid in silver. In the early days of the Yishuv, the local orange – which was at the center of Argov’s organized labor campaign – came to symbolize Israeli agricultural industriousness.

For background on the formation and actions of the Jewish Brigade during World War II, see – among countless books, articles and studies – this short write-up on the Yad Vashem website. For a more personal account of the “life and times” of the Jewish Brigade, see this article by Rami Litani, the son of brigade sergeant-major Eliyahu Litani.

Finally, for background on Israel’s first Do’ar Ivri postage stamps, see this 1958 article from the Davar daily (Hebrew), and this English-language write-up from the Society of Israel Philatelists.

Mitch Ginsburg and Lev Cohen are the senior producers of Signed, Sealed, Delivered? This episode was mixed by Sela Waisblum. Zev Levi scored and sound designed it with music from Blue Dot Sessions. Our music consultants are Tomer Kariv and Yoni Turner, and our dubber is Leon Feldman.

The end song is Kol HaDrachim Movilot LeRoma (lyrics – Itzhak Itzhak (Itzhak Ben-Israel), music – Zvi Ben-Yosef, arrangement – Mordechai Shelef), performed by Havurat Shoham and Giora Ross.

This series is dedicated to the memory of David Harman, who was a true believer in the values of the Declaration of Independence, in Zionism, in democracy and – most of all – in equality.