We’ve got four featured moo-ers: a red heifer that some think will bring the messiah, a cow that’s become the symbol of radical Israeli veganism, buffalos that hold the future for a self-described “Israeli redneck,” and the golden calf that was biblical big-business.

Cowabunga!

First, a look at the massive effort to find a red heifer, powered by people who believe such a cow needs to be found before the messiah can come.

Mishy Harman (narration): OK, so like many everyday expressions, no one’s totally sure where ‘Holy Cow’ comes from. Obviously, many linguists point East, you know, the whole sacred cows in India business. Some others give credit to Batman and Robin, and, then there’s a bunch of popularizers. Famously, of course, the Yankees’ Phil Rizzuto, whose catchphrase even ended up on a Seinfeld episode.

Jerry Seinfeld: What is that?

George Costanza: Ah!! Steinbrenner gave them to us! In honor of Phil Rizzuto being inducted into the Hall of Fame.

Phil Rizzuto: Holy Cow!

[laughter]

Mishy Harman (narration): And yeah, just looking at Wikipedia here for a sec [sounds of typing] baseball seems to feature dominantly in the Holy Cow history. I’m reading here, “the phrase appears to have been adopted as a means to avoid penalties for using obscene or indecent language.” OK, baseball in Israel… not so big. But for some people here, holy cows couldn’t be a more serious business. This is from an Australian TV show from the late 90’s called Animal X.

Animal X Narrator: It’s an eternal mystery, and the answer to a prophecy: The appearance of an animal, said to be capable of changing the world.

Mishy Harman (narration): Just in case you think this is some arcane theory, no no no. The Animal X guys clarify that the stakes couldn’t be higher.

Animal X Narrator: Scholars believe the appearance of a new red heifer portends the building of a new temple. And after that, the Old Testament says, God will appear, as a Messiah to change the world.

Mishy Harman (narration): If you’re not familiar with this sacrificial saga, here’s what they’re talking about: In the book of Numbers in the Bible there’s a passage about red heifers, which says that the only way the Israelites could purify themselves was by sacrificing a red heifer, a totally red cow, through and through, and mixing its ashes with some water. This, the people who believe these kinds of prophecies contend, is critical for rebuilding the Holy Temple in Jerusalem and well, setting the stage for the messiah. So all around the world there are people trying to breed a red heifer. It’s sort of this cattle husbandry subculture which brings together Orthodox Jews, Evangelical Christians, ranchers, cattle breeders, and messianics of all stripes. Rabbi Chaim Richman is originally from Massachusetts, but has lived in Israel for more than thirty years. He’s part of the Temple Institute, Machon HaMikdash, which is a private organization dedicated to preparing everything necessary for building a new temple and performing all the biblical rituals: Harps, lyres, priestly robes, alters, decanters. Richman’s the one who monitors the births of red heifers around the world. Here he’s talking about it in a Temple Institute YouTube clip.

Chaim Richman: Here, every time a red heifer is sighted, we try to stay on top of the situation, we try to be informed. There have been a number of red heifers born in recent years, that have become disqualified for one reason or another.

Mishy Harman (narration): That’s right, this can’t just be any old red cow. Here are some of the things that disqualify these small rustcolored calves from being *the* red heifer: A blemish, a nick, spots, a couple of nonred hairs. From time to time a red calf is born which seems to fit the bill. In 1996, Shmaria Shore, from Kfar Hasidim, near the Carmel, thought he had a winner. He called her Tzlil, or Melody.

Shmaria Shore: We’ve put her here in solitary confinement. The other cows will not bother her. And we have not shaved off her horns, she has not been branded, her ears have not been pierced.

Mishy Harman (narration): This was big news around the world. The Boston Globe reported that Tzlil was protected by an “armed guard in a skullcap,” a prominent Israeli columnist worried about the explosive geopolitical consequences of actually sacrificing her on the Temple Mount suggested that she be shot at once. But in the end it didn’t pan out. Those damn white hairs… Then, in early 2014, the red heifer world was once again a buzz. Here’s another Temple Institute interview with Rabbi Richman. As you’ll hear, the clip was live from the scene of action, so chirping birds, a running brook, the whole thing.

Yitzhak: Rabbi, what are we looking at right here?

Chaim Richman: Yitzhak, we are looking at some exciting new footage that we have just received of a brand new red heifer that was born somewhere in the United States, we’re not going to be more specific, for security purposes.

Mishy Harman (narration): They called her Talia.

Chaim Richman: We’re all excited about this one and watching with intense anticipation.

Mishy Harman (narration): But by August, Richman announced in a short blog post, Talia too was no longer fit for her holy task. A patch of her skin had changed its pigmentation. There was clearly a lot of disappointment. But he isn’t giving up.

Chaim Richman: If you really want to know the truth about the red heifer, if you really want to have all the answers, you can’t. Because God tells us that there are things in this world that are bigger than us. So today people have all kinds of questions about the red heifer. Who? What? When? Where? Why? Some of these questions we can answer. Some of them we can’t answer. And some of them we won’t answer. Do we have a red heifer today? Do we have candidates for the restoration of purity? Yes, there are red heifers today.

269 was originally the number of a a sweet-looking slaughterhouse-bound calf. Now it’s the namesake of 269, a radical vegan movement spawned by Sasha Bojoor, that uses the rallying cry, “Free 269.” Yochai Maital talks with Sasha to trace the origins of 269 and their extreme tactics.

|

|

Mishy Harman (narration): If you’ve dined out in Tel Aviv lately, you might have noticed a whole new section on the menu of many restaurants vegan dishes. Of course this is true in many places around the world, but in Israel the movement seems to be particularly rockin’. Before we begin, I just want to say that there are a few pretty graphic moments in this next piece, that might be hard for you to hear. Just take that into account. Here’s Yochai Maital.

Yochai Maital (narration): When God searched for words to describe the small territory into which he was leading Moses and the people of Israel, he came up with the “land of milk and honey.” Arnon Oshri, a third generation dairy farmer from Kfar Vitkin, loves that catchphrase. Actually, he loves it so much, that he drew a mural of it on the outer wall of his storage house.

Arnon Oshri: It’s a combination of a cow and a bee. It’s the land of milk and honey, so I created a combination of a cowbee [laughs].

Yochai Maital (narration): But if the biblical copywriters wanted to be even more accurate, they might have called it the “land of chickens and eggs.” Ever since the late 90’s chicken consumption here has been on the rise: peaking at 38 kilos of chicken meat per person per year. Second only to the Americans. Most of those chickens are processed in one of six slaughterhouses, working around the clock to satisfy our growing appetite for shawarma, shishlik, and the occasional chicken soup. All this sustains a flourishing 4.6 billion Shekel industry.

Sasha Boojor [Hebrew]: For those who don’t know, we are now going to the Poultry Council. They’re located on Kaplan Street, in Tel Aviv, on the junction with Ibn Gabirol. It’s this big building… the guys there have two floors: The fourth and the fifth floors.

Yochai Maital (narration): It’s 6am in a small flat in Tel Aviv. About a dozen radical vegan activists are crammed in the living room. they fill the air with morning breath and smoke from their rolled up cigarettes. Sasha, the leader — black pants, tight black shirt, a stern gaze — is debriefing the group on today’s mission: Barging into the headquarters of the ‘Egg and Poultry Association’ the main organization responsible for our schnitzels and shakshuka.

Sasha Boojor [Hebrew]: We’re going in there with trays… with dead chicks on the trays.

Yochai Maital (narration): “Were going in there with trays full of dead chicks,” he explains calmly. As he’s talking, some of the the activists are busy pouring a few bucket loads of dead chicks onto plainlooking dining hall trays. They collected the carcasses the night before from the dumpsters of the Nordia hatchery, near Netanya. The hatchery sells laying hens, so male chicks are basically useless waste and are either put into big black plastic bags and tossed away, or else shredded by specialized industrial grinding machines. The activists’ plan is to deliver these trays of dead chicks to the offices of the administrators who are supposedly responsible for their death.

Sasha Boojor [Hebrew]: And basically you offer these trays to the employees who are responsible for the death of those chicks.

Yochai Maital (narration): Later that morning, the group shows up at the ‘Egg and Poultry Association,’ in a fancy office building in the center of Tel Aviv. They all cram into the elevator along with their trays, squeeze bottles of fake blood, and a huge sign that reads “the people here are responsible for the final solution of 15,000 chicks every day.”

[Hebrew]

Employee: Hello.

Activist: Is Mister CEO in?

Employee: Get out of here.

Activist: Mister chickkiller?

Employee: What do you want from me?! [shrieking]. Ronit, Ronit, come to me!

Employee: What are you doing here?

Yochai Maital (narration): Immediately, all hell breaks loose: One secretary tries to lock herself in a side office, but Sasha blocks the door with his foot and barges in with a platter of chicks. “What’s wrong,” he asks, “you afraid to look? Here are your victims! The chicks you’ve thrown in the trash!”

[Hebrew]

Activist: Come with me! What happened, are you afraid to see? Here are your victims, the chicks that you throw into the trash. They died slowly in the containers. You can sit behind your desk and sign off on the execution of millions of chicks, but you don’t want to confront the results?

Employee: I’m just a clerk! What do you want from me??

Activist: But you’re signing off on executions, all those numbers are animals.

Employee: But I’m not the one who decides! Do me a favor and leave me alone, I’ve already had enough.

Yochai Maital (narration): “What do you want from me?” one of them shrieks. “I don’t make any decisions. I’m just a clerk.” Other, slightly braver employees, confront the intruders.

[all this is in Hebrew]

Employee: You’re talking about slaughter, not murder.

Activist: You have blood on your hands.

Employee: You’re an idiot! Enough with your nonsense. You should be ashamed of acting this way!

Activist: Take responsibility for your actions.

Employee: Get out! You and all your friends. You’re disrupting our work.

Yochai Maital (narration): “You have blood on your hands!” “You’re an idiot!”… They go back and forth like this for a while. Meanwhile, a couple of activists manage to break into the CEO’s office. They’re trashing it: Pouring buckets of dead chicks and squirting fake blood all over his desk. Pretty soon, a plump police officer with a gentle smile arrives on the scene. He peaks in, seems a bit anxious, and radios in for backup.

Cop [hebrew]: I’m not under pressure, I’m just asking for help, that’s all.

Yochai Maital (narration): A few minutes later four police cars arrive, and a whole bunch of grumpy cops sluggishly enter the building. This is clearly not terribly exciting for them.

[Hebrew]

Cop: Come to the elevator, fourth floor Fahdi. Are you ready to get up or not?

Activist: You’re being violent.

Cop: Are you ready to get up or not?

Cop: He refuses. Come on, drag him out…

Yochai Maital (narration): The activists refuse to disperse, so the cops handcuff them, drag them out, and whiz them off to the Yarkon police station.

[Hebrew]

Cop: They’re under arrest, you cannot approach them… thank you.

Yochai Maital (narration): By the evening they’re all released, back at home, busy planning their next operation. Eventually police arrive on the scene and arrest some of the activists. This group is called 269. They’re a new vegan organization who thrive on staging shocking operations. Sort of the local PETA. Like most popular movements, they have a leader and a mascot. First, the leader.

Sasha Boojor: Yeah, my name is Sasha Bojoor, the founder of 269 life.

Yochai Maital (narration): Sasha’s an unlikely leader for a radical movement. He’s an introvert, even anticharismatic.

Sasha Boojor: For me, this is not the lifestyle that I would choose. I’m a very private person, and I like to keep to myself and stuff, so it’s very hard for me to be always surrounded with people and not having space for myself and stuff.

Yochai Maital: So what would be your chosen lifestyle?

Sasha Boojor: Like being in a closed dark room, by myself, being quit. this is something that be very nice for me.

Yochai Maital (narration): But he soldiers on. For him, only one thing matters: The cause. Sasha wasn’t always so dedicated to animal rights. When he was five, he moved to Israel with his mother and sister. His father stayed behind in Moldova.

Shasha Boojor: It was a bummer. You know it was hard for everybody in my family also. Things were very tense and people in my family started changing… I didn’t really like it here.

Yochai Maital (narration): In Israel, Sasha kept to himself. He hardly had any friends, and became a quiet, reclusive kid. After school he’d spend his afternoons feeding stray neighborhood cats. But that’s more or less where his animal loving ended. His diet at the time, he told me, consisted of two components: Meat and ketchup. One of his favorite dishes was chicken legs. Not the pulke, the actual foot.

Sasha Boojor: Where you see the actual fingers and stuff.

Yochai Maital: You can eat that?

Sasha Boojor: Yeah, yeah. Russian people like it.

Yochai Maital (narration): Sasha tells me about his childhood in Israel as a young immigrant from Moldova. One day, when he was sixteen, he noticed a flier a classmate had pinned to the billboard. It was about animal rights and veganism. For some reason, he’s not really sure why anymore, it caught his attention. He read it, and became curious. In fact, he became so curious that he began to skip school and visit dairy farms, hatcheries and slaughterhouses.

Sasha Boojor: Once you see and hear the smells and the screaming and the dead and dying animals, it just becomes much more personal for you. The shock was so big, and it gave me a lot of motivation and clarity on the topic. The things that I saw was things that will be with me until I die.

Yochai Maital (narration): It probably won’t surprise you to hear that before long Sasha became a vegetarian, then a vegan, and finally an activist. His school attendance plummeted. He joined Anonymous, a local animal rights advocacy group, and stood on street corners for hours, trying to put pamphlets in people’s hands. Now remember, Sasha really isn’t a people person, so spending entire days trying to talk to strangers… He describes it as hell.

Sasha Boojor: Yeah it was awful, you know…

Yochai Maital (narration): most of the people he tried talking to just ignored him, others, would actually lash out, screaming at him.

Sasha Boojor: You get to a place which is very dark. You get to a point of so much anger and stuff that just becomes like a quiet disdain.

Yochai Maital (narration): But he kept at it.

Sasha Boojor: Ten years, something like this.

Yochai Maital (narration): Ten years! Sasha didn’t graduate from high school, or go to the army with his fellow classmates.Unlike his other activist friends, Sasha was willing to take risks. He wanted to carry out ballsy plans that would get noticed, that would shake people out of their apathy. But first, he needed a mascot. Sidewalk canvassing was the one constant in his life. Day in, day out. And during all those countless hours of trying mainly futilely to proselytize bypassers, Sasha had plenty of time to contemplate.

Shasha Boojor: We are seen as a week bunch, like a bunch of hippies. It’s a very weak image.

Yochai Maital (narration): a different approach began forming in his mind, ballsy plans that would get noticed, that would shake people out of their apathy. He talked to his fellow activists, But they shot him down every time. His plans seemed too radical, and dangerous. Ultimately, Sasha decided to quit and start his own operation. But he knew he needed some help. someone, maybe something, who could rally the troops. He was looking for a mascot. So he and two activist friends got in a small Fiat and headed north. Here’s one of them, Nikita.

Nikita (dubbed): We got to the farm, jumped the fence [laughs] and started walking around. Most of the calves were very scared and timid. It was almost impossible to snap any good pictures. But then we noticed this cute white calf who was really friendly and excited. He let us touch him, play with him. His branding number was 269, and I just said: “This, this is the one!”

Yochai Maital (narration): 269, a small white baby calf, was everything you could ever want from a mascot: Cute, photogenic, relatable, and, most importantly, he had a short and catchy number.

Sasha Boojor: Three numbers is very sexy thing. But when it come to four numbers, five numbers, much less attractive.

Yochai Maital (narration): Especially if your planing to brand that number on to your skin… Now that he had a mascot, Sasha was finally ready to stage his first action. The inauguration of the 269 movement took place in October 2012, at Rabin Square, in the center of Tel Aviv. Sasha and two other activists, all symbolizing cattle, were penned up in a makeshift barbed wire cage. One by one they were dragged to center stage and the digits 269 were branded on their flesh with hot iron.

Sasha Boojor: I felt like my skin got ripped off, like the skin stick to the iron and was peeled. Very uncomfortable because like you can smell the skin boiling.

Yochai Maital (narration): Sasha went home, bandaged his wounds and uploaded the video of the event to YouTube.

Sasha Boojor: Almost immediately it went viral, and it spread like wildfire.

Yochai Maital (narration): It got more than 200,000 hits within a couple of weeks. People from all over the world who had seen the clip started to contact Sasha. Other 269 brandings followed in Bratislava, Buenos Aires, London, Capetown, and many other places… Mexico City, Prague, London, leeds, Valencia, Cape Town, Iowa city, Grosseto, Moscow, Buenos Aires, Paris, Krakow, Amsterdam, SauPaolo, Bratislava… [list goes to under and fades] They all rallied around the same mantra “Free 269.” Meanwhile back In Israel, Sasha’s group was making new headlines. On one infamous occasion, Tel Aviv residents woke up to find decapitated heads of cattle atop fountains with reddyed water. Another public action was staged on Yom haatzmaut Israeli Independence Day, our annual mangal or barbeque day. 269’ers showed up at a popular picnic spot, set up grills and started cooking carcasses of… cats and dogs. As you can hear, this wasn’t going down so well… Children began to cry, their parents got mad, an angry crowd started gathering, and the 269 activists were beaten pretty badly. The police were on the scene within minutes, and without thinking twice, arrested Sasha and his comrades. But their most shocking performance was staged on a busy boulevard in Tel Aviv. One of the 269ers lingered on the sidewalk, as if she was just a regular bystander. She was holding a newborn baby in her arms.

[woman starts screaming]

Suddenly, four masked men emerged from behind. One ripped the baby out of her hands, two restrained her, and the fourth tore her shirt open and began violently milking her breasts.

[woman continues to scream for help]

Even knowing that this woman is an actress, and that the whole things is staged, somehow doesn’t make the tape less disturbing.

[her screams intensify]

269’s public displays are hard to stomach. It isn’t pleasant to wake up in the morning, walk down to the bus stop and be greeted by a severed head staring up at you from a pool of blood. But, for others, the blow has been more concrete, affecting their livelihood directly.

News: “And now we turn to the organization of 269 Life, that’s its the name… They claim to work for animals. In practice, they are breaking the law. Tonight they announced that they broke into a coop in central Israel and released the chickens.”

“They claim to work for animals, in practice they are breaking the law,” one news anchor concluded before reporting on a series of thefts from chicken coops and dairy farms. Marcus Ben Elias, a dairy farmer from Kibbutz Gezer, showed me a video from his security cameras: Two thirty in the afternoon, two teenage girls approach the gate, clumsily load a calf into the hatchback of their car, and take off.

Marcus Ben Elias (dubbed): One calf… if I do a quick calculation here… costs something like 50 to 80 thousand Shekels. So say I’m against capitalism: Am I allowed to go into a bank and steal money? I do not know, where do we want to go?

I don’t know, how far do you want to go with this?

I don’t know, how far do you want to take this?

I don’t know, how extreme do you want to get?

Arnon Oshri: You can’t cross this border. Once you cross this border there is no limit.

Yochai Maital (narration): This is Arnon Oshri, painter of the beecow. To him, this is all quite simple. These people are thieves, outlaws.

Arnon Oshri: What happened in the Wild West for cattle thieves? they were shot on the place. if somebody is breaking in and trying to steal, he is risking his life. simple as that. we will not be tolerant to people coming to steal. But I will suggest to these people. do know the border. because if you cross it, somebody might get hurt.

Yochai Maital (narration): And it’s not just about lost income or stolen property. It’s also a matter of personal safety.

Arnon Oshri: And if you can see pictures in the net of a woman pointing a gun and saying zero tolerance to animals abuser, and I guess being a dairy farmer, I’m an animal abuser in their view, the next step will be a murder, and we know that words can kill and pictures can do the same.

Yochai Maital (narration): Lots of people are horrified by 269’s tactics. Even some vegan activists feel such radical measures are alienating the public and inciting hate. But for others around the world, the group is striking a chord. It’s attracted adherents from many other countries, including this guy, Uze Ozon, from Turkey:

Uze Ozon: Shasha Bojoor is an inspiration to the people of my country. I believe that in like two hundred years, Sasha will be taught in schools, like Martin Luther King and other great people in history.

Yochai Maital (narration): There’s also a Cairo branch and it has even reached Tehran.

Iranian 269er: These people are like angels on the earth, God bless them.

Yochai Maital (narration): Back home, in Israel, still, thousands of people are getting tattooed with the 269 logo. And that tattoo has come to represent more than a personal philosophy it’s a kind of proof of membership. See, when you go vegan in Israel, you enter a sort of club, and 269 are sort of the commando unit of this club. And… Having such a cute mascot, doesn’t hurt either… Still, many people in Israel see this all as not much more than a passing trend. So is veganism really a thing here?

Ori Shavit: Definitely veganism is a thing in Israel, there is no doubt about it.

Yochai Maital (narration): This is Ori Shavit, prominent food writer, recentlyturned vegan activist.

Ori Shavit: I never wrote a single word about veganism up to three and a half years ago. And that’s all I did was to write about foods and trends and diet and what’s going on. So there is no doubt that something has changed dramatically. Today Israel is supposed to be a leading nation in the word in the percentage of people who call themself or treat himself as vegan, of course we don’t know what everyone eats.

Yochai Maital (narration): Well actually we kind of do. Israel’s Central Bureau of Statistics keeps incredibly detailed charts of our total food consumption. Remember that chicken gold rush I told you about in the beginning? Well, in recent years, our chicken cravings seem to have tapered off. 2012 actually saw a four percent drop in chicken meat consumption, and it seems that this trend is true of other animalderived food products too. At the same time, the market for vegan staples, like almond milk and soy cheese, is booming. Vegans see all this as early signs of a greater change. Dairy farmers, Arnon and Marcus and many other experts, don’t contest those statistics, but they disagree on the causes, blaming it all on the recession and pointing to a general dip in spending. A recent national poll might suggest that they’re right. It estimates that only two percent of the population are vegan. In Tel Aviv, which is generally seen as the hub of Israeli veganism, their estimates go down to one percent. Other surveys, put that number higher. Actually as high as 5%. Whatever its actual reach, veganism has definitely entered the conversation here in a pretty big way, tagging itself on to a long list of contentious topics. Meanwhile, totally oblivious to the war raged in his name, 269, the calf, who’s not really a calf anymore (more like a huge bull) is spending his days in leisure. A few days before he was due to be slaughtered, 269 was stolen or liberated, depending on how you look at all of this, by terrorists or animalloving activists, again, depending on how you see the whole thing. He now lives a peaceful incognito life, noshing on the grass in an undisclosed location. As for his brothers and sisters, I think it’s safe to assume they’ve long since found themselves in our pitas.

Mishy Harman (narration): That was Yochai Maital. Yochai’s one of the producers of our show. Our next story takes us far away from the 269 demonstrations. Very far. I spent the past year living in Madison, Wisconsin. Now as you can imagine, there weren’t too many Israelis around. Polar vortex… Not really our thing… So when it turned out that my parents’ friend Zev had a daughter and soninlaw who live nearby, I called them up and they invited me over for lunch. These kinds of meals with Israelis living abroad usually follow a pretty similar pattern: First we try to figure out who we know in common, then we eat and have a heated conversation about Israeli politics, next some inevitable jokes about how bad American hummus is and how everyone misses Bamba, and finally… weather comparisons. Always the weather comparisons. I usually budget two hours, end up staying three, and leave feeling a little bit homesick… But my visit with Dubi Ayalon and his family, didn’t follow that pattern. Not even close. To get to Dubi’s you head about forty miles northwest of Madison. Once the houses disappear and are replaced with endless cornfields and farms with red barns and silvery silos, you reach Plain. Plain, Wisconsin. Population 773. It’s name seems to fit it just right. Plain’s got a Culvers, which is like the local McDonald’s, a gas station, post office, single row of stores, and that’s … basically it. Now let’s on keep going. About five miles north of Plain, literally [car switch turned off] in the middle of nowhere, [car door closes] there’s a purple farm house [knock on the door] and a silo with a big Star of David in the middle. They say Israelis are everywhere, but this is really the last place you’d think you’d find them.

Dubi Ayalon: Cocococome in!

Dubi Ayalon, a retired IDF lieutenant-colonel, traded a life as a school principal in Israel for a life of raising and miking water buffalo in rural Wisconsin. Mishy Harman went to the farm and spoke to Dubi.

|

|

Dubi Ayalon: [Singing] Avinu malkenu.

Dubi Ayalon: My name is Dubi.

Dubi Ayalon: [Singing] Chonenu anenu.

Dubi Ayalon: I am now sixtyone, fuck I’m old. Sixtyone.

Dubi Ayalon: [Singing] Avinu malkenu, chonenu anenu.

Dubi Ayalon: I came from the Holy Land right into the holy shit.

Dubi Ayalon: [Singing] Ki ein banu ma’asim.

Dubi Ayalon: I live in the middle of nowhere, somewhere in Wisconsin, and I am the first Israeli redneck living in the US.

Mishy Harman (narration): Dubi spends his days milking water buffaloes.

Dubi Ayalon: Fucking bloody redneck. Spending in a bloody barn, freezing to death because of it’s fucking cold outside, and milking buffaloes, okay! A big deal! But nevermind, I mean.. Fuck it.

Dubi Ayalon: [Singing] Ase imanu tzedaka va’chesed ve’hushienu.

Mishy Harman (narration): Maybe its been a while since your last visit to the zoo, so a quick refresher. Water buffaloes. Imagine a cow, a *really* large cow. Now add big horns curling backwards, a dark brown, or black, hairy coat, and huge, powerful, muscles. Some of Dubi’s buffaloes are out in snow, calmly roaming around, jets of frozen air coming out of their nostrils. But most of them are huddled together at the end of the barn. Barely moving. Just staring, skeptically, right at us. There’s something majestic about them. Unlike cows, they’re basically wild, and do whatever they want. In Italy buffalo farms are a dime a dozen. Huge ones, with hundreds of animals. That’s where all that buffalo mozzarella comes from. But in America it never really caught on. So as far as he knows, Dubi, with his herd of thirty, is actually the largest milking buffalo farm in the country. At the end of every week a pickup truck from the Cedar Grove Cheese Company pulls up beside his barn, and sucks up all the milk he’s collected. At the height of the milking season that’s roughly 125 gallons, which go to the dairy company for about 12 dollars a gallon or about eight times more than a gallon of cow’s milk.

Mishy Harman: Do you like buffalo milk?

Dubi Ayalon: I like the milk I don’t eat the cheese.

Mishy Harman: Why?

Dubi Ayalon: Yuck.

Mishy Harman: What is the difference between buffalo milk and regular milk?

Dubi Ayalon: Ah— it’s the same difference between gold and shit. Simple as that. Buffalo milk is very rich. It’s a very tasty milk, the smell is a little bit different. And it’s healthier. Way healthier than… cow’s milk. So, the difference between shit and gold. Now the farmers around me will kill me because of this sentence. [chuckle]

First snow of the season. Started this morning, and the wind is blowing, and it’s fucking cold. It’s fucking cold. [singing] Hey buffalo, hello buffalo. Hey chiquita, you gave birth last night. Hey buff easy buffalo, easy buffalo. Come 24 Come Sheli.

Mishy Harman (narration): To call this a family operation wouldn’t quite do it justice. It’s more like a Dubi operation. He gets up at 4:30am, in the Wisconsin winters, and works by himself. Milking buffaloes is hard. And looking at Dubi, you can tell. His hands are all cracked and craggy. He’s short and wiry. You can see he’s super tough.

Dubi Ayalon: [comes up from under] This is a new one, [buffalo crying] just born last night. Come chiquita! [buffalo crying] Hey chiquita! [buffalo sound] hey buffalo, it’s okay little one. It’s ok. [Buffalo crying].

Dubi Ayalon: Yeah, my day begins with, uh, hebrew pray. [singing] Avinu malkenu… It’s a beautiful song. And then the buffaloes are coming into the barn.

Mishy Harman: Oh you sing to them. That brings them in?

Dubi Ayalon: Yeah, yeah. This song brings them in, not because of my beautiful voice but because they know that after the song there are treats.

Mishy Harman: So, like god, basically.

Dubi Ayalon: [laughs] I will say nothing about it. So with this song they are coming to the barn, milking, chores. If I’m lucky, I’m back home around ten, tenthirty at night. That’s my day. Routine sweet routine. The farm is a very small farm, fiftysomething acres. Pretty much isolated from the environment. We are in the middle of nowhere. My wife came with idea of water buffalo. I started to, like, research it, and I fell in love with this animal.

Mishy Harman: Why?

Dubi Ayalon: It’s gentle, in one hand, it’s powerful in the other hand. I love the buffaloes. There’s nothing to say, I love my buffaloes, as simple as that. Unlike cows, are not dumb. They have some kind of personality, and it’s a challenge because you cannot control them. You need to seduce them, not to control them. I used to be a control freak. I cannot be a control freak here. As simple as that. I mean it doesn’t work. You are not the king of the world. You are part of it. I used to, you know, shoot orders: “Make sure that this will happen by tomorrow morning.” And now I’m being controlled by… I dunno, around thirty buffaloes, that they can do whatever the buffalo wish to do. And I am part of them. When I’m milking in the milking season, I smell like buffalo. Sometimes I behave like buffalo. So, that’s farming, anyhow…

Mishy Harman (narration): Before he settled here, eight years ago, Dubi had a previous life. Those orders that he used to shout, they were in the Israeli Army, where Dubi was a Lieutenant Colonel.

Dubi Ayalon: I was in the army for twentyfour years, yeah, twenty four years. Holy crap, that’s a lot. I loved the army. The army was a place that I could find my… place, and I enjoyed it.

Mishy Harman (narration): Dubi went as far as he could go in the army. After that, he wasn’t really ready to part with uniforms altogether. So he joined the police. That lasted for eight months. He left, he says, because he was a terrible cop. He had way too much sympathy for the criminals.

Dubi Ayalon: And then I went to this, prestige, academical institution, a school of educational leadership, wow what a name, for two years. And then I became a school principal of a regional school in Nahalal. Those kids are nice, but they are BORING, as my kid would say. Nice kids, really obsessed about their degrees and bullshit like this. [Throat noise of disgust] I mean, you are a kid. You see what I mean? Be… creative, be mean, be something! I got bored. So, I resigned and went to a vocational school of bad kids. I liked it, I must say, I liked it. They were challenging. They were… everything beside routine. One of my kids was… brought to trial because of killing someone… Another one… came up to be a drug dealer. And they weren’t interested in learning, and you needed to come to the point that you will be respected by them not because of what you are but because of who you are. They will respect you because of what you are doing. How you behave. Can they trust you. But then I made a mistake.

Mishy Harman (narration): On a field trip, Dubi went to check in on some particularly rowdy kids. No sooner did he walk in then one of them locked the door behind him, so all of them, Dubi and the loud kids, were stuck in there together. Then, well, as Dubi says, he “kicked the shit” out of the ringleader.

Dubi Ayalon: And, that’s some kind of mistake that you don’t do. Big mistake. Something that shouldn’t happened, but it happened, so I resigned. I mean, I couldn’t forgive myself because of it. After you are kicking the… beating one of the students, you cannot ask the other students to be… not to use violence. It’s a bad joke. You should be a role model. And, so I…I…I just resigned, and then was a decision to move to the…United States and…and, you know, start again from scratch. And, that’s it. We ended here.

Mishy Harman (narration): When he first arrived, Dubi had very clear opinions about Americans, and especially American farmers.

Dubi Ayalon: I used to think about the farmer as a redneck. Dumb, loud, and… arrogant. My neighbors… heavy duty religious one think I belong to the chosen ones. What chosen and what fuck….

Mishy Harman (narration): But it didn’t take too long for him to warm up to the other dairy farmers around him.

Dubi Ayalon: They helped me in a way that this farm wouldn’t exist without my neighbors, as simple as that. Everybody around think that I’m an idiot milking water buffaloes [rough mocking voice] Ah well a lieutenant-colonel, well a school principal, how the fuck you milking buffaloes? But it doesn’t bother them, or it doesn’t stop them to help me in a way that sometimes I’m standing aside and saying to myself that we, the Israelis, are very proud about how… eh, eh, eh, kind of eh, eh, community we have, how much we are helping each other. We have a lot to learn. Let’s put it this way. A lot. The smell is the smell of buffalo manure, and the tick that you are hearing is the electric fence, so they will stay. This is chiquita. Last night, sometime last night she calved after giving me hard time till it happened. Look at her udders — holy crap how much milk you have there. Nice. Some of them has Hebrew names. All the ones that were born here have Hebrew names. The one on the left, her name is pussy. The big one behind her, the brown one, her name is Chiquita. The one on the other side, her name is Einshem. Next to her Nechama. Next to her, Broken Horns. Heyyyyy….

Mishy Harman: And uh, what was it like leaving Israel for you?

Dubi Ayalon: The hardest thing about leaving Israel was leaving my kids there. All the rest, I could handle.

Mishy Harman (narration): Dubi has four children. The youngest, Erez, came with him to Plain. But his three older daughters from his first marriage, all in their twenties then, stayed in Israel. They’re constantly emailing and WhatsApping, but they say it’s rough. The biggest challenge for them wasn’t that he now lived half way around the world. It was that he was changing. Becoming a new person.

Dubi Ayalon: I mean, books are nice, I don’t have the time to read. I lost the passion to read. My daughters got pissed because it’s resemble the change in their father from the person that was a bookmaniac, obsessive reader, he became to be, a redneck, so, they don’t like it. I don’t think my personality changed—my behavior changed. I … used to think that if I will look tough, talk tough, it will make me tough. I am the same lamb that I am today. There is no, there is only like costume. Hey OhFive, Hey OhFive. Let’s stand inside. wah wah wha…! Fuck it is cold! Hey buffalo. [door clang].

Mishy Harman: What does it feel like to be so far away from home?

Dubi Ayalon: I am not a part of this society 100%, and I am not any more a part of the Israeli society 100%. So when I am coming to Israel for example, the… landscape, the views, the smells, the food is part of my childhood and being a grownup, but the other thing around it drives me nuts. So I am coming here. When I am coming here I am missing the parts that are in Israel. I’m not comfortable 100% in both places. I am still a stranger, and I believe I will be a stranger all my life here. And Israel is still my homeland in a way that I cannot explain it’s something in your feelings. [sighs and chuckles]. So, my truck looks like a piece of shit, and my house — I used to have a bigger house, a nicer house in a nicer neighborhood. Am I less happy? No. I am happy here. I’m just fucking happy. I am fucking singing every morning, do you sing every morning?

Mishy Harman: No.

Dubi Ayalon: Exactly! So, that’s it.

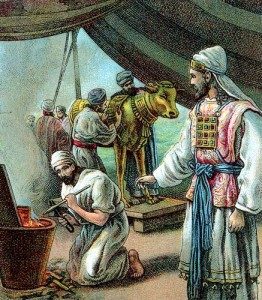

Writer and radio host Jonathan Goldstein offers us a sly and bittersweet interpretation of Moses’ battle against idol worship, told from the perspective of the youngest employee of a golden calf business that faces its fiercest competition yet: God.

Jonathan Goldstein is the host of the radio show and podcast Wiretap. This story comes from his book “Ladies and Gentlemen, The Bible!”

Jonathan Goldstein (narration): After forty intense days with God, Moses descended Mount Sinai, his nerves shot. No sooner had he reached the base of the mountain than he heard music coming from a nearby clearing. Peering through the trees, Moses saw the children of Israel praying to what appeared to be a crudely sculpted golden calf. They danced and pranced — flounced, frisked, strutted, and swaggered. All hopped up on idol worship.

Cranky by disposition but made even more irritable by lack of sleep, Moses began to weep tears of anger. Even the people he’d trusted — the wise, loyal ones — tapping their feet and snapping their fingers like it was a hootenanny!

Golden calves were all the rage, but Moses had warned them before he left. “I’ll be down in a jiff,” he had said, “so don’t start praying until I get back.”

Seeing their lurid dance, Moses took the tablets he was carrying – bearing commandments that, among other things, commanded them to worship no other god but God god – and dropped them to the ground. Though Moses could get angrier than just about anyone besides God, he dropped the tablets not in his wrath. For Moses this was odd, as he ate, spoke, slept and even snored in his wrath. He could even whistle a tune in his wrath! But when he let the tablets fall to the earth, he did it like an overburdened little kid who just didn’t care anymore. That was when Moses was at his scariest: when he was all quiet and holding back.

And so, when with tightly closed eyes and a warble in his voice, he instructed the idol-worshiping children of Israel to burn the calf, grind it to powder, mix the powder with water and drink it, they did not ask “can gold burn?” or “can gold be drunk?” as they did not want to make Moses any angrier than he already was. “Zero commandments for you,” he repeated quietly under his breath.

You would think that that would spell the end for golden calves, but this was not the case. There was still one man holding out hope, a man who thought monotheism just another fad. And this man’s name was Gomer, and he was the largest golden calf dealer in the Sinai region, and much to his son Ian’s embarrassment, he had a real “never say die” attitude.

“They’ll come around,” Gomer said to his son soon after the commandment episode. “An invisible god that no one can see except Moses? Oh, and He’s also got a temper problem — likes to make threats and burn bushes. How do you even begin to pray to someone like that? I don’t want to pray like a frightened mouse. I want to pray as one equal to another. And all those laws — ‘don’t wear this cloth with that cloth! Don’t let this cattle graze with that cattle!’ All that red tape. Not for me.”

But, the god of Moses did make a splash with a great many people. When Moses got going, waving his staff around while yelling bloody murder — curing leprosy and transforming his rod into a snake — he made a pretty persuasive case. People became fired up on New God and began forming mobs of protest in front of Gomer’s showroom. But still, Gomer was undeterred.

His confidence wasn’t for nothing. After all, Ian’s father was an innovator. When he got into the business it was strictly cows, full grown, but Gomer saw that as homes got smaller, there was a need for an idol that could fit more neatly into a corner — something you could drape a caftan over and prop your feet on when you weren’t worshipping. And thus the mini cow, or “calf,” was born.

“What makes the god of Moses better than my calves?” Gomer asked. “What can he do that they can’t? Speak in that sonorous voice that makes you feel like you just swallowed your own tonsils? Bullcrap. That’s not being a god. That’s just being pushy. The Calf is a more laid back, cud-chewing lord. He minds his own business and only steps in in a pinch. Remember when I prayed for the S.O.B. selling silver calves next door to get dropsy? And did he not get dropsy? All praise the Golden Bovine, whose golden teats nourish us with invisible golden milk.”

Gomer stopped his pantomime of teat-squeezing and looked at his son to see if he was making an impression.

“But you heard Moses talk on the mountain,” Ian said, “the deep grumbly voice — the water into blood. It gave everyone the same feeling. We all said so: The tingling in the chest. The rattling of the rib cage. You said you felt it, too.”

“You know me,” Gomer said. “I don’t want to hurt feelings. If someone gets excited I get excited, too. But someone does a few magic tricks and you renounce everything you ever stood for? I was born a Golden Calf man and I shall die a Golden Calf man. Integrity. It’s the way my daddy raised me and, if I’m not mistaken, it’s how I raised you.”

Actually, Gomer had raised him to be cheap, suspicious, and sneaky. Ian didn’t know where integrity fit in.

“They’ll come around,” Gomer maintained. But as the days went by and the angry calf-hating crowds grew in number, Gomer saw that people were not coming around.

“What we need is a battle plan,” he said.

And so Gomer invited over his brothers. A bigger bunch of shysters, hoodwinkers, and chicanerous pettifoggers there never was. Ian hated when they all got together. In five minutes the whole house smelled of farts and his cheeks were pinched black and blue.

Ian, wanting to avoid the ordeal of their visit, offered to voyage out to purchase dried fruit, but Gomer told him to stay put.

“I have a whole warehouse full of the golden fuckers,” said Gomer, for this was the way he talked when he was with his brothers. It was fucker this and fucking fuck-balls that.

“We have to tactically leverage this,” said brother number one. “We have to rebrand,” added brother number two.

When they were all together, they became one big fat “we.” Ian would try to get into the spirit of it and “we” along with them, but his “we’s” always got caught in his throat.

“The name ‘Golden Calf’ scares people,” said brother number three gravely. “We could start calling them ‘Festive Cows.’”

“But ‘Golden Calf’ is a name the public knows,” Gomer reminded them.

“We have to distance ourselves from all that,” said brother number one, “we can sell cow clothes. Dress ‘em up in the latest styles. Tunics! Prayer shawls! Princess Golden Cow

for girls. Slap a beard on the S.O.B. and you’ve got a Moses Cow. We’ll call him ‘Mooses.’ “It’s still a golden calf,” said Ian. “It’s just different names for what it is: an idol.”

“Just a different name,” said brother number two, “look at the weeping willow. Would you seek its shade were it called an overflowing barf bucket bush?”

Then Ian felt his cheek clamped, twisted, pulled, and finally snapped back into place. “Jackass,” his uncle said with affection.

During the ten plagues, if the brothers had lived in Egypt, they’d have seen each plague as a distinct business opportunity. Cursed darkness? Let’s-make-babies night! Hail

“Can’t we just melt them down and get into a new business?” asked Ian.

“What kind of new business?” brother number one asked, pinching his cheek with warmth.

“Something a little less…contentious,” said Ian.

For Gomer and his brothers the case was closed, but Ian still worried. When he’d go outside to try and calm the agitated crowd, he’d end up learning a lot about New God. New God had made man in his own image and his résumé was really impressive: divided the Heavens from the Earth, made man from the dust, created the universe — the list went on and on.

“What can your god do?” the crowd demanded.

Never any good under the gun, Ian stuttered and back-pedaled.

“You can polish him,” he said, “and lean against him, too.”

The Golden Calf is strictly local,” said an intense and scholarly-looking young man named Rodney.

“You mustn’t even speak His actual name!” interrupted Rodney. “He doesn’t like it, so we’ve invented nicknames for Him, such as: He Who Will Kill You. He Who Will Crush You, and He Who Will Set You On Fire and Douse the Flames with the Blood of Those

You Love. You really have to be careful because he hears all and sees all.”

Ian felt New God’s gaze upon him all the time now. Especially when he was lying in bed. He was scared of this new god and sometimes even believed he could smell Him. When there was burning in the air, he pictured the angry smoke escaping New God’s ears. He worried that every little thing he did, every word that escaped his lips, was ticking off New God in some way. It was too much to bear.

“The consummate god is a forgiving god,” they said on the street. Still, he was scared. For himself and for his father.

And then the rioting began. “No more idols!” they chanted. “Our god trumps all gods.” Gomer remained unimpressed.

“For such a powerful god,”he said, “Invisible God is surprisingly thin-skinned.”

“Ours is a jealous god,” said Ian.

Gomer was struck silent by his son’s words. He stared at Ian a good long time. As a rule, Gomer was never nonplussed. But his son’s words — they nonplussed him.

“I see,” Gomer said, nervously massaging coins through the thin leather of his money pouch. “So now he’s your god.”

“There’s no choice,” Ian said. “He’s taking over.”

“I don’t get it,” said Gomer. When you were little, you adored the god of your father.” Gomer reached over and pinched his son’s cheeks with sadness.

“What happened?” he asked.

“He’s omnipotent,” said Ian, using a word he’d just learned from Rodney. “He can outfight, outthink, and outrace any god you throw at Him.”

“Look, I’ll get my brothers back in here and we’ll cook up a new god — newer than New God. We’ll call him ‘Omnipotent Plus One’!”

“This is embarrassing,” Ian said. “It’s also dangerous.”

“I didn’t realize I was embarrassing you,” Gomer said, his pinching fingers limp.

That night, Gomer remained in the showroom, pacing from calf to calf, ruminating.

“What is there for a father to pass down to a son if not his god?” Gomer wondered.

He did not like this new god. He was uncanny, grandiose, and bloodthirsty, but Gomer could also sense that he might actually have staying power.

And so, the very next day, he brought in the alchemists with their enormous black cauldrons. He knew it would likely mean taking a tremendous beating on the value and he knew it would mean having to shout his brothers down, but Gomer vowed that every last golden hock and udder would be melted. His new idea was to remold the gold into long, thin wands with pointing little index fingers at the tip.

“We’ll market them as commandment pointers,” said Gomer, “to help you read the word of God. You know… God god.”

The brothers mulled it over. After a long silence, they spoke.

“Give the people what they want,” said brother number one, who knew when to stand down.

“Gold is gold,” said brother number two.

“Yep,” said brother number three distractedly, for in his mind he was already on to a dozen other hog swindles.

Ian watched the calves melt, their little calf faces poking out of the pots, looking at him. They made him feel almost as guilty as the sight of his father’s face, which was wet and glowing in the heat of the showroom.

When he was a child, Ian could pray so hard. Harder than anyone he knew. It was his thing. He’d squint his eyes, and scrunch up his face. He’d look like he was going to burst a blood vessel, his hands in fists, hoping — willing the world to be a certain way. For the house to quiet down. For good things to happen. For Gomer to notice what a good

prayer he was.

When he would finish praying and he’d look around and the world was pretty much the way it had always been, the one thing he knew he could rely on was that the Calf was keeping count, giving out points for effort. At least the Calf knew how hard he was trying.

New God made sense to him, but the Calf made sense to his heart. It was such a part of his childhood — like the smell of certain foods or the tunes his father whistled when they took long walks together.

As the years wore on, Ian would often invite Gomer to come and pray with him to New God, and Gomer would tag along and pray — but Ian could always tell his father was just doing it to make him happy.

When Gomer finally died it was at a ripe old age and when Ian prayed for him, prayed for his safe passage in the hereafter, inevitably, more often than not, it was the Calf that he saw.

“Please don’t think of the Calf,” he would say to himself as he prayed, but the harder he prayed and thought about trying not to think about the Calf, the more the Calf would enter his thoughts and prayers. After some years had passed, Ian eventually got used to the intrusions and just stopped trying to fight them. In his mind, he imagined his golden man-headed cow, or cow-headed man, and he just prayed the best he could.

For music and mixing help on today’s episode, a big thanks to Jonathan Groubert, Anny Celci, and Nathan Bowles. Thanks also to Benny Becker, Daniel Estrin, Karen Carlson, Mihal Davis, Michal Ayalon and Aeyal Raz. Julie Subrin’s our executive producer. Israel Story is produced by Mishy Harman, Yochai Maital, Roee Gilron, Shai Satran, Nava Winkler, and Maya Kosover.